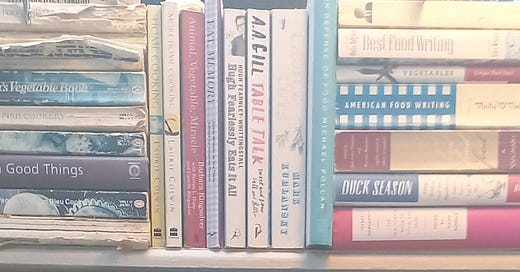

As a Food Writer, I’m lucky to get sent cookbooks for review. I have hundreds. So many I have decreasing amounts of shelving for those I want to keep. The rest I stack outside my front door for passers-by to scoop up. (Perhaps I should list the ones they ignore - publishers might be quite surprised.)

For years, my mother, a fine cook, owned only one cookbook. Like many British women of her generation, it was Elizabeth David’s seminal A Book of Mediterranean Food published in 1950, 4 years before the end of rationing in post-war Britain. It spoke lyrically of red peppers, olive oil (only available in the UK in chemists as a cure for earache), artichokes, and other alien vegetables.

When I read it, I was scornful. How could anyone properly cook anything when oven temperatures were vaguely defined as Cold, Moderate, or Hot? My mother regarded me with greater scorn. In the 1950s, those were the heats stamped on an oven’s dial.

In Britain, traditionally upon their marriage new wives were given a copy of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. Published in 1861, it was a Victorian guide to running a household with highly structured recipes helpfully illustrated. It is still available, and still wrapped up in wedding paper.

Perhaps the US equivalent might be The Betty Crocker Cookbook first published in 1950, since when over 75 million copies have been sold. Betty Crocker was a character invented by the PR department of the company that later became General Mills and first promoted on The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air, which began broadcasting in 1924 from Minneapolis, the company’s base.

Le Ménagier de Paris beat both of these manuals to the subject, by several centuries. Written back in 1393 in the fictional voice of an elderly husband addressing a younger wife, it was a guide to a woman on the proper behaviour in marriage and how to run a household, and included sexual advice, gardening tips, and recipes.

The world’s first known book focusing exclusively on cooking is considered to be De Re Coquinaria, a Roman collection of recipes from 5th century AD, widely but not exclusively credited to Apicius, who contributed about three-fifths of its recipes.

He was a gourmet who squandered his wealth on food. When he was down to his last million sestertii, he invited his circle to what must have been an epic banquet. In today’s price of gold, 1 sersterce equals $3.25. (There’s no point giving you the price in pounds as, from this week, these are now worth diddlysquat.) During the last course, Apicius poisoned himself. You might suppose a $3 million feast would render the need for poison unnecessary.

In the 10th century AD, The Book of Dishes, the earliest known Arabic cookbook, containing over 600 recipes, was produced by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq. Two centuries later, a book of the same name by Muhammad bin Hasan al-Baghdadi appeared, as did The Mānasollāsa by King Someshvara III of the Kalyani Chalukya dynasty of south India, a text covering divers subjects that included food. Some time in the 13th or 14th century in China, Hu Sihui wrote Important Principles Of Food And Drink. Also in the 14th century, the cooks of Richard II wrote the oldest known English cookbook, containing 196 recipes.

So far, so many men. The first female writer of a cookbook was English. A Choice Manuall, or Rare and Select Secrets in Physick and Chyrurgery: Collected, and Practised by the Right Honourable, the Countesse of Kent, Late Deceased, a collection of medical recipes, was published in 1653, two years after Elizabeth Grey’s death.

While it took several centuries before recipes were collected into cookbooks, the first ever solo recipe, for making flatbread, was found on the walls of the 19th century BC Egyptian tomb of a woman called Senet, on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t to pass on to others but to make sure she was fed in the afterlife.

Two centuries later, three hand-sized Assyrian tablets were discovered in Ancient Mesopotamia with recipes for 21 meat-based and 4 vegetable-based stews and a bird recipe that might, with its nose-to-tail use of parts, have been constructed by a chef of today:

“Carefully lay out the fowls on a platter; spread over them the chopped pieces of gizzard and pluck, as well as the small sêpêtu breads which have been baked in the oven; sprinkle the whole with sauce, cover with the prepared crust and send to the table.” (Sêpêtu may be dill seed.)

A recipe from 14th century BC for Sumerian beer made from bread sounds not unlike today’s fermented black bread, sweet-sour Russian drink, kvas.

The earliest known single British recipe is one involving nettles boiled with barley and water. Recorded in 6th century BC, suspicions are that it is likely to have been created two centuries before that.

There has always been a compulsion among people passionate about food to share information on how to create it. Whether as single recipes or in collections of them, as soon as humans discovered the means of conveying them to a wide audience, it seems they were anxious to pass on good recipes. These days, the popular medium is the internet. There is barely any need to buy a cookbook. If you know what you want to cook, you can just call it up. But if you don’t, or if you only want to fantasise about a marvellous meal you haven’t the energy to create, reading a cookbook is almost as satisfying as the food.

One of my mother’s favourite recipes by Elizabeth David is from the Piedmont and celebrates the last of good summer tomatoes - though it shines with lesser ones. It makes a good one-dish meal or an excellent side dish to a roast.

1 red pepper per person (absolutely not a green one), with or without stalk

1 fat clove of garlic per person, peeled, or more to taste

1 or ½ an anchovy fillet

1 large ripe red tomato or 3-4 cherry tomatoes per half pepper

salt and pepper

generous glug of olive oil, to create a flavoured sauce to mop up

basil leaves

Preheat oven to 180C/350F.

Cut each pepper in half lengthways and scrape out all the seeds. Set upright in an oiled baking dish so they don’t fall over.

Finely slice the garlic and distribute it inside the peppers. Lay an anchovy fillet on top inside each pepper. If you’re not an anchovy fan, use half a fillet - it adds depth and will melt away during the cooking.

Halve the tomatoes and press one half into each half pepper. Season with salt and pepper then drizzle very generously with olive oil. (By tucking the garlic slivers and anchovy under the tomato, the garlic won’t burn and turn bitter and the anchovy will be invisible to its opponents.)

Roast for 45 minutes or until the edges of the peppers and tomatoes are beginning to char and caramelise around their edges.

Remove from oven and top with a few basil leaves. Serve with crusty bread or ciabatta to soak up the juices and perhaps a green salad with a garlicky vinaigrette.

I collect recipes, but never leave comments. This is the exception. My husband and I were blown away by how something so very easy could be so amazingly good. I followed it to the letter, with one tiny change - a sheet pan instead of a baking dish, to give me room for the two bone in, with skin, chicken breasts and a handful of baby red potatoes, sliced in half. It was wonderful. I did throw a few thyme stems over the whole thing. What happened to the potatoes was pure alchemy.

Thank you!