Global warming (the original, more precise descriptive now diluted into the less anxiety-inducing ‘climate change’) is made real for those who aren't immediate victims by media coverage of floods and fires. But quietly affecting in the background are the alterations in seasons. In the middle of July, I picked more plump and juicy blackberries than I usually do when I most expect them - one month later, towards the end of August.

Blackberry picking is one of those activities designed to pacify children for free. Give them a jam jar, a small basket, a sandcastle pail to fill, and you can keep them placidly occupied for, oh, around eight minutes. Or, with luck and the promise of an ice cream, an hour or more.

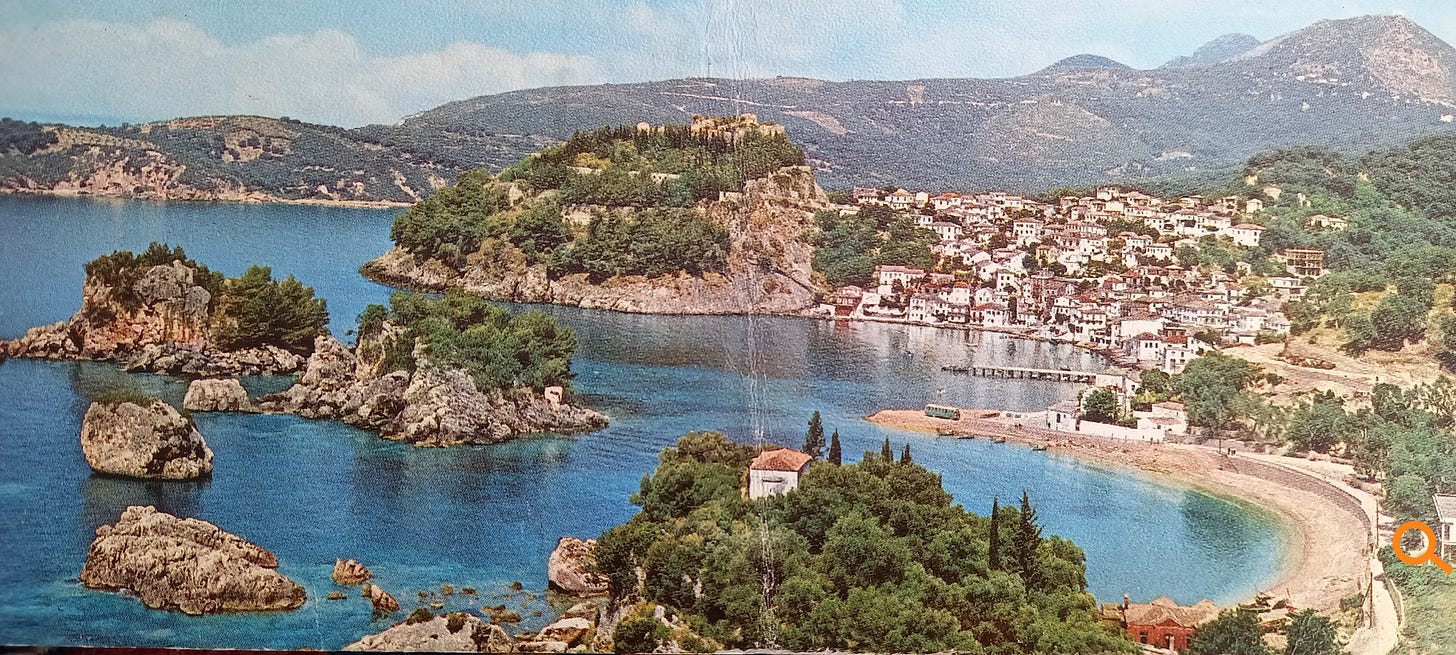

Along with mushrooms and hazelnuts, blackberries are one of Nature’s greatest free field treasures. Yet not every culture appreciates them. When I lived in a tiny cottage behind a beach on the top left hand corner of Greece, the yiayias of the village took me in hand as a hopeless case who would undoubtedly starve to death through her lack of knowledge of the treasures growing wild around her. We would trudge across the mountainside to dig up askolimbi (Golden Thistle) for roots that tasted like artichokes. We would forage in spring for young dandelions, wild fennel, and rocket (arugula), sorrel, chicory, mustard greens, and paniers of so much more. Most of these ‘horta’ - greens or, less politely, weeds - were boiled or steamed, and served with rich green olive oil pressed from the olives of their own groves, and a generous squeeze of a fat lemon from another of their trees that dropped their fruits onto the decorated paving stones of the narrow streets beyond their whitewashed stone garden walls.

When autumn came, I fully expected we would be back in the fields to collect the blackberries that scrambled profusely over the rocky terrain. But, no. They avoided these, claiming they encouraged stomach ache and had no merit. I went surreptitiously on my own to harvest them, took them home to poach with a little sugar, then delivered jars of blackberries to each yiayia. ‘Yiayia’ is the name assigned to any Greek woman of a certain age whether or not she is in fact a grandmother. I encouraged them to try a little of the compote with the thick goat’s milk yogurt they made. The ones who did, did so out of courtesy because it was clear I wasn’t going to leave their kitchens until I had seen them taste it. Also, I had a warmer relationship with them than I did with the other yiayias who were convinced I had only appeared in the isolated village to poach not blackberries but their husbands and sons.

No-one fell ill. With astonished delight and suddenly ignited by the enthusiasm of cooks everywhere who have discovered something new, those yiayias persuaded their sceptical neighbours that the fruit was not only safe but delicious, and then the whole village swarmed over the blackberry bushes.

Despite their distrust, blackberries have been eaten for millenia. ‘Haraldskær Woman’, a woman preserved in a Danish bog dating from 490 BC and unearthed by peat workers in 1835, had remains of blackberries in her stomach. Growing in the wild right across Europe as well as in Asia, it’s believed they were used medicinally by Native Americans to treat problems at both extremities of the body - sore throats and diarrhea - and to dye animal skins. They turned the tough blackberry vines into heavy-duty twine. The Romans added them to honey and wine to create a very pleasing drink. (The recipe for mine - and I hope yours - is in the next paragraph.) Medieval Europeans made them into jams, jellies and pies. But by the 17th century, like my yiayias they became suspicious of them, convinced they caused stomach ache, and blackberries fell out of favour except for use as clothing dye.

By the 18th century their popularity was restored and the pies returned to tables. Under a lid of pastry or crumble we respect them as the natural partner of apples, the two fruits maturing simultaneously - before climate change intervened. They make a marvellously scented jam and if that’s your plan, pick a quantity of unripe red berries to add to the poaching pan. These will emphasise the flavour and add extra essential pectin to set the jelly. For a liqueur to sip at the end of a meal or add to white or sparkling wine as an alternative to Crème de cassis or pour over vanilla ice cream, I fill the third of a storage jar with them, sprinkle in 3 or 4 tablespoons of sugar then add a bottle of vodka and leave the berries to steep for as many months as I can forget about them. (Once this was four years later, when I moved house and discovered the Mason jar at the back of the coal hole, the berries and alcohol converted into a sumptuous liqueur.)

Blackberries make a lovely sauce to serve with duck. While other game is generally associated with autumn dining, in my view, duck comes into its own in the summer. Duck confit crosses both seasons; but when the barbecue is glowing, a duck breast slung on top to crisp its skin then turned to grill its fleshy underside and left to rest a while before eating with a simple salad of leaves dressed with a mustardy vinaigrette and a handful of toasted walnut halves, is one of the treats of balmy evenings.

It is elevated further by this sauce on the side which also works brilliantly with a roast duck. I adapted it from the recipe for blackcurrant sauce developed for duck by Michel Troisgros. I was once on a panel with him judging a bunch of terrified French chefs who had to produce an original foie gras recipe with an appropriately paired wine. An afternoon of foie gras and wine - oh, the demands of life…(Forgive the boast, but it gives me such a lift to remember, and honestly, if at some happy moment you’ve some name or event to drop, boast away. Non?)

Michel Troisgros is the grandson of one of the longest lines of modern French restaurateurs. The Troisgros brothers - his father and uncle - were themselves sons of Jean-Baptiste Troigros who, in 1930, started the eponymous restaurant in Roanne near Dijon, given its first Michelin star in 1955. In 1957, his sons Jean and Pierre took it over, renaming it Les Frères Troisgros. Their second Michelin was awarded in 1965, followed in 1968 by the much sought-after and prestigious third star. Michel, the grandson, oversees a Troisgros empire-ette and still holds 3 stars. The sauce of his grandparents is one worth having in your arsenal for tizzying up not just duck but other game.

300g/10oz blackberries

1 flat tablespoon caster sugar

5 tablespoons wine vinegar

1 tablespoon blackberry jelly or red currant jelly or blackcurrant jam

2 tablespoons Crème de cassis

250ml/8 fl oz stock

juices from the roasted duck

90g/3 oz butter

Stew the blackberries in 5 tablespoons of water.

In a small pan, reduce the vinegar and jelly to a sticky caramel and deglaze with the Crème de cassis. Stir in the stock to loosen and smooth it out, then add to the blackberries and simmer for 20 minutes. Pour the juices of the duck into a gras-maigre if you have one (a jug with a high spout one side and a low spout the other so the fat rises to the top and doesn’t invade the juices being poured out from the base). Or thoroughly skim off the fats. Simmer 5 minutes more then strain through a sieve into a clean pan, pressing lightly on the fruit to release all its juices but not its murk. Reheat then whisk in the butter just before serving.

I have an idea: all subscribers get to go on a tour of north-west Greece with Julia, to go foraging with the yiayias!

In my youthful foraging days in Vermont, the late-summer blackberries were the least interesting of the seasonal wild berries I gathered. They had barely any flavor, and very little pulp or juice surrounding their multitude of seeds. Earlier in the summer, there was a type of blackberry, called a dewberry by the locals, that grew close to the ground in the old pastures, not on canes, which made them difficult to gather, as it required moving about on one's knees. Dewberries were plump and juicy, and resembled the blackberries you describe. they reminded me a bit of the marionberries I had found in Washington State, though the dewberries lacked their ambrosial aroma and flavor. My foraging these days is sorely limited, but I happily buy cultivated berries from the local farmers who grow them.