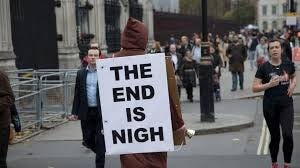

We’re confronting the end of so much familiar to us. Not quite the world yet. But freedom of speech? Viable newspaper circulations? Government support for the arts, science, public transport, social responsibility? Correct use of apostrophes?

Under threat in the food world is pretty much all that we’ve been so used to eating for so long we haven’t given it much thought: the roast chicken dinner; meat; affordable coffee and chocolate. The death of blueberries? Quite possibly. Now fish.

Not too long ago, we were being urged to reduce our meat consumption for the sake of climate change and look to fish for our protein supply. Fish farming is a vital contributor to global food security, an industry projected to reach $444.38 billion/£334.60 billion by 2029 that produced around 130.9 million tonnes of fish in 2022.

To supply a growing market, fish farms have expanded at an astonishing rate - some even on land in Norway, Switzerland, British Columbia, Iceland, Lesotho, the UK, the USA, the United Arab Emirates. We’ve already been alerted to the problems surrounding some fish farms. Too many are hotbeds of infestation, lice accumulating on the bodies of fish to the point they need regular dosing with antibiotics. Their faeces infect the floor of the ocean beneath them and bottom-feeding marine life. Escapees can breed with wild fish, weakening the genetic makeup of native stocks.

Now a deadly parasite is devastating global fish farms, so far at a cost to the industry of more than $66 million/£50 million a year.

A group of microscopic parasites called myxozoa have been discovered in the Amazon infecting fish with lethal diseases that include kidney disease in salmon, swim bladder inflammation in carp, and gill disease in catfish. The Amazon may be nowhere near where you live. But the parasites, hidden inside their hosts, threaten all fish, given they survive in marine environments as well as freshwater ones.

More than half the fish examined in the Amazon basin were found to be infected, endangering local fish farming, biodiversity, and recreational fishing. In parts of the western USA, similar parasites have killed off as much as 90 percent of trout populations. Though less commonly, these myxozoa can also infect amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Scientists are working urgently to prevent the spread of the parasites. They’ve set up a floating lab on the Amazon because, says marine biotechnology Professor Paul Long of King’s College London, “The diversity of life in the Amazon basin is undisputed and still little-known.”

There is hope. “To our surprise,” he reports, “we uncovered a new process of gene regulation that was previously believed not to exist in these parasites.” The team is now looking into how these genes are turned on and off to develop gene-based vaccines to control fish pathogens.

“Studies on these parasites are essential for developing strategies to control or reduce their impact on the health of farmed fish,” says Dr Santiago Benites de Padua, manager of the Brazilian Fish Company and a veterinarian. Whether the vaccines will carry, like antibiotics, through to diners of the fish was not part of the report.

Fish farming is not new. It began in the 1730s when a German naturalist experimented with taking salmon eggs from streams and trying to hatch them. By the early 19th century, hatcheries were being built in Europe to raise fish to supplement wild stocks, in decline even then. While their success was limited, by the 1960s the salmon farming industry was under way with Norwegian farmers using cages floating in fjords to raise Atlantic salmon fattened on special feed. Today, salmon raised in net pens, predominantly off the coasts of Norway and Chile, account for 70 percent of the 3.7 million tons eaten globally each year.

At any fishmonger, it’s hard to tell whether your farmed fish comes from a good- or poor-practice operation. Some countries are more regulated than others, with salmon from Scotland, the Faroes, Iceland and Norway less likely to be affected by lice - though it isn’t guaranteed. The Soil Association, the UK body that certifies everything organic, has threatened to withdraw from the Scottish salmon sector without significant improvement to environment and fish welfare practices. Chile, whose farmed salmon farming is among the cheapest on the market, faces ongoing challenges over its impact on the environment despite regulations, as do the fish farms of Brazil and Argentina.

But if we’re to avoid farmed fish and eat only line-caught fish, unless that method, too, is stiffly regulated, it would quickly deplete stocks of those. Already, wild fisheries (which don’t include line-caught fish) contribute up to 83.3 million tonnes, a trillion and more of individual fish up to half of which, unsuitable for market, are reduced to fishmeal and oil that - think about this - go to feed farmed fish and farm animals. Some trawlers use complex gear and nets up to 240 metres wide by 160 meters deep which, strung up to 30 together, can reach for miles. Other trawlers dredging the ocean floor destroy the marine environment. Off the west coast of Scotland, Norwegian dredgers for scallops kill off the sand eels that feed puffins as well as the immature scallops growing into the next generation.

Which puts us back to the argument that just about the only protein we can reliably consume without harm to supplies or the environment are insects. I don’t see that playing well yet. (Although you won’t be short of supplies of processed food. This attack on UK government food policy by the industrial food complex won’t be action limited to Britain.)

If you’re not lucky enough to have access to fishmongers supplied by small family-run fishing boats using thoughtful techniques, the best option is a diet rich in legumes and vegetables, nutrient-dense food offering a wide range of minerals, vitamins, fibre and proteins. We’re familiar with the vegetables-and-olive-oil based Mediterranean diet. But the countries of the Middle East thrive on legumes and pulses.

I love fennel at this time of year. Shaved on a mandolin into paper-thin discs, with thin slices of orange and slivers of endives all lightly soused in a garlicky vinaigrette with a handful of toasted almond flakes tossed over all, it makes a tinglingly fresh salad I eat often - sometimes just on its own or with a chunk of goat’s cheese. Otherwise, I stew it slowly in lemon and olive oil to serve as a side vegetable or lay on top of a mound of polenta that has a generous cup of Parmesan cheese folded in.

Serves 2 as a side dish or as a main course with polenta

2 large heads of fennel (or 1 large head with polenta and halve the remaining ingredients except for the lemon)

1 large lemon

80 ml olive oil

120 ml water

tablespoon of coriander seeds, lightly crushed

salt and pepper to taste

Slice off the stalks and discard but reserve any fennel leaves. Finely chop those. Carefully trim the root so that the leaves are still attached. Slice from top to bottom in half along the fattest length then each half into three separate pieces, all leaves attached to the root.

Lay on the pieces their sides in a lidded pan large enough to take them all in one layer. Squeeze over the lemon juice, scatter in the coriander seeds, dribble over the olive oil, add by the water. Season and set the lid a little askew and simmer over a low heat.

Stew until the fennel is soft and begins to caramelise and the liquid has almost evaporated, about 30 minutes. Turn the fennel half way through and if too much liquid still remains, remove the lid to allow it to steam away, leaving an emulsified lemon sauce. Serve on warmed platter as a side dish to a main event, or lay on top of a mound of polenta cooked according to the packet that has had a generous packed cup of grated Parmesan and a lump of butter folded in. Scrape the oily juices from the bottom of the pan onto the fennel, sprinkle over the fennel leaves and serve.

Thanks again for an insightful, balanced article & lovely-sounding recipe. I live in the mideast of the US; buying fish at the docks is not an option here. The closest would be the Great Lakes supply of perch, walleye, salmon, whitefish, trout, etc, which we do enjoy. As you point out, the fish supply chain cannot always be trusted. Our local purveyors rely on industry certifications and standards, but even those have been the subject of criticism. Until then, I continue to eat nearly anything and everything (except anything endangered) while rationalizing that balance, quality, and portion control are enough to keep me healthy.

I gave up farmed fish decades ago. Being in the bread basket of America, I was appalled when entrepreneurs started fish farming in formerly highly artificial fertilized and pesticide rich farm land. No thanks.

About your later comment regarding soft pasta vs firmer, take a look at the glycemic index. Soft angel hair pasta is like shooting sugar in your veins! Practically premasticated!!! It’s why it’s better to eat whole fruit than to drink a smoothie. The only energy consumed with smoothies and the washing up of your blender! Regarding insects I ate a BBQ’d grasshopper once. Kinda’ like a potato chip.