Just what a chicken needs. Says the grapevine.

A recipe for Wine-braised chicken with roasted grapes

In the ‘Which came first, the chicken or the egg’ department, there are ingredients in cooking that are almost forced together by dint of their maturing around the same time. Blackberries in an apple crumble are a marriage made in English railway hotel heaven. Especially with custard. Baked red cabbage adds acidity as well as colour to bland turkey, rich goose and dark-meat game birds, along with hearty autumn stews. (I confess I‘ve never taken to it raw as in those worthy salads served in health-food cafes with rough-hewn table tops that give their Birkenstock-wearing diners splinters. It’s like chewing a naked toothbrush - spiky, zero flavour and a jaw work-out.)

Grapes are at their best right now, and good paired. But what with?

Bottom of my personal list of possibilities (which I consider the only place for them) is the cheese plate. The grape’s eyeball pop in a mouthful of Brie or Cheddar is just ghoulish. Discuss.

But one of the grape’s most seductive partners is chicken.

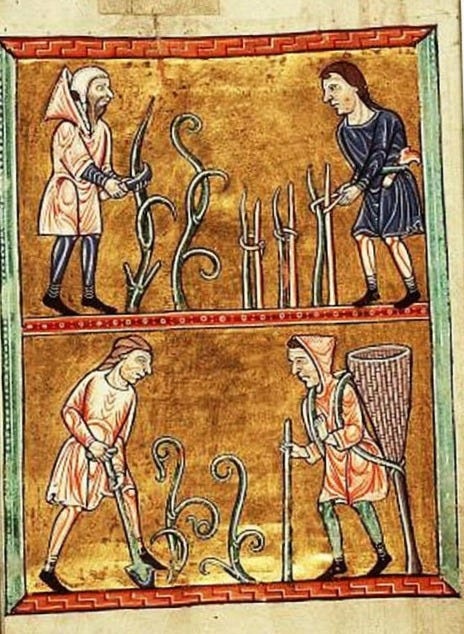

The combining fruits with meats is nothing new. Early archaeological records show man would have eaten whatever he found, mixing insects, fruits, leaves and plants together in his diet. I picture him slouching through the undergrowth hunched over some small crunchy thing like me at a party’s salted nuts bowl. Just as today across the Middle East and North Africa, so the early inhabitants of Persia and Canaan served meats with nuts and fruits - apricots, prunes, quince, plums, barberries, pomegranates, nuts, and raisins. Which, of course, are dried grapes.

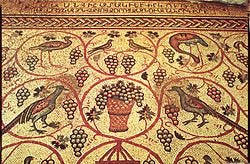

Grapes first appeared around 6000 years ago, near Tbilisi in Georgia, cultivated not only for eating but for turning into wine. Neolithic wine-making took place in the fertile valleys of the South Caucasus with vine cultivation spreading swiftly to the wider region that included northern Iran and Armenia.

The oldest known winery was discovered in 2011 in Armenia by an Armenian-Irish team excavating in the three-chambered Areni-1 cave. Dating to around 4100 BC (900 years before comparable wine remains were found in Egyptian tombs), it contained all that was necessary to make wine, from a shallow basin in which to trample the grapes, to fermentation jars, and storage vats. Grape seeds and the remains of pressed grapes were found, and branches of dried vines. Those grape seeds came from the common grape vine, Vitis vinifera, a grape still used to make wine.

The first written and pictorial records of vine cultivation date back to 2500 BC. Around 1000 BC, trading - or marauding - Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans began spreading vine root stocks across the Middle East and Mediterranean. Around the 6th century BC, vines were introduced into Southern Gaul - today’s France - with the arrival of Greek and Phoenician sailors into the port of Marseille.

While grapes have predominantly been channelled into creating wines, dishes have been devised to celebrate them. In French cuisine, any dish called ‘Véronique’ involves grapes, either as an ingredient or a decoration. Responsible for this is August Escoffier, chef from 1890 at London’s Savoy Hotel. He created the classic Sole Véronique fish dish of grapes with a cream-and-vermouth sauce in 1898 to celebrate the London run of ‘Véronique’, a comic opera by André Messager, a French composer. The libretto, by Georges Duval and Albert Vanloo, is set in 1840 Paris and concerns a young woman who pretends to be a flower seller to avoid the advances of an irresponsible but dashing aristocrat, only to fall for him later when he becomes less of a rake. The opera remains a popular part of the French operatic repertoire.

Grapes are full of all manner of health-giving multi-syllabic properties in unpronounceable combinations. Most recently popular was resveratrol, a natural plant compound and antioxidant found in red grapes and consequently red wine, which some touted as a life extender. As yet, there isn’t any strong scientific evidence to back that claim. But any excuse for a glass of plonk.

This non-Véronique grape and chicken dish isn’t rich as is one of those, but instead fresh-tasting. While it does contain wine, it has no cream. It’s a lovely autumn celebration, easy to put together and forget about until time to eat it.

Serves 4

4 medium onions, peeled

600g potatoes, peeled

2 large heads of fennel

1.5kg/3lbs 3oz free-range chicken, jointed into 8 pieces

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

3 tablespoons olive oil

½ bunch fresh rosemary, leaves roughly chopped

300ml/10 fl oz white wine

200ml/6¾ fl oz chicken stock

1 head of garlic, broken into cloves

1 lemon, scrubbed and thinly sliced

2 handfuls red grapes, preferably seedless

Leaves from a few sprigs of fresh flat-leaf parsley, roughly chopped

Preheat oven 190C/375F.

Cut onions into wedges, roughly chop potatoes. Shave fennel bulbs with a potato peeler then cut into six vertical chunks, keeping its layers attached to the base.

Season chicken. Heat oil in a large saucepan over a medium heat. Working in batches, add the chicken and fry until gold all over then remove to a plate. Add more oil if needed.

Reduce heat to medium-low, add onions and fennel and saute gently until soft but not coloured, about 15 minutes. Return chicken to pan, add rosemary, raise heat to medium-high and leave chicken to colour a few minutes.

Pour in wine and bring to boil, then lower heat and reduce by half. Add stock and potatoes. Insert garlic cloves between chicken pieces and bring pan gently back to boil.

Transfer all to a roasting tray, slip lemon slices between chicken pieces and vegetables. Roast 30 minutes or until potatoes are tender and chicken cooked through.

After 10 minutes, put the grapes in a small roasting dish, drizzle with a little oil and roast in oven for the last 20 minutes or until caramelised. Fold the grapes into the chicken pieces. Pick off and roughly chop parsley leaves, scatter over and serve.

This sounds great and I will try it. And - it made me stop and think about how quickly winemaking must have spread from region to region.

My husband decided at some point that he didn't like dishes that combined meat with fruit. <sigh>. It happened after he met me, because his mother was an undventurous cook and his family's rare outing to a restaurant involved finding a place where his father could get a martini and a slab of prime rib. He will tolerate the occasional agrodolce dishes served to him, like my family recipes for winter borscht or stuffed cabbage, although in the latter, he won't eat any of the prunes. He is going birdwatching with friends in Morocco in January. Interested to hear about the sorts of tagines he will be served and whether any included fruit. Maybe if he eats it there, he will let me make something similar at home.