Sensitive to cultural appropriation as we have become, along with statues and artifacts should we be ditching the recipes we have culled from our imperialist history? Never again cook anything from Madhur Jaffrey’s seminal Invitation to Indian Cooking? (Not even her chicken korma?) How about Claudia Roden’s Book of Middle Eastern Food? Diane Kennedy's The Art of Mexican Cooking or Maricel Presilla’s Gran Cocina Latina? Never eat another hamburger outside the US? Or Adobo outside the Phillippines? If we aren’t Jewish, should we never open another cookbook by Joan Nathan again?

It would be a backward step of self-deprivation, given how much we can learn about other people through their food. Doesn’t each single one of the massive global sales of every Ottolenghi cookbook published represent a ‘soft-entry’ into an unfamiliar culture?

Other peoples’ food is generally delicious - though I’m reserving my opinion of Iceland’s hákarl. Aside from the tactical invasion of Iceland by the Royal Navy during World War II - ‘Operation Fork’ (see how everything ends up referring to food?) - it’s a country that hasn’t been a popular target for empirical takeover. If it had been, who knows if that fermented shark wouldn’t now have a regular place on British tables at mid-week school-night suppers?

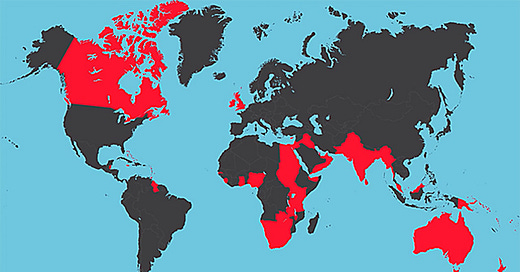

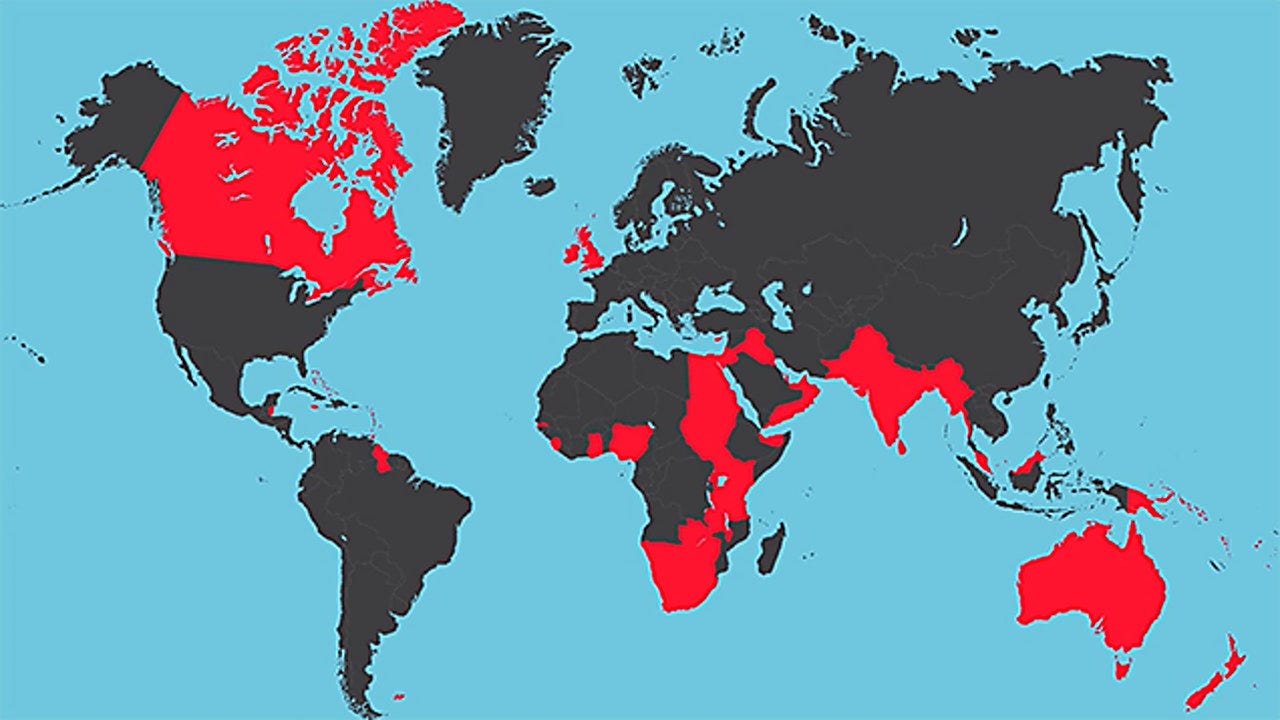

Anyone doubtful of the positive contribution of its colonies upon a nation's eating habits should look at the ethnic restaurants in those countries which went empire-building or dabbled in geo-politics.

Britain's favourite food is Indian, chicken tikka masala widely considered the national dish. Pre Brexit, curry houses employed 100,000 people and had annual sales of 4.2 billion pounds ($5.17bn). In the US capital, where the Wilson Boulevard is nicknamed the Ho Chi Minh trail, you can't move without running into a Vietnamese eatery, Ethiopian restaurant, Central American pupuseria or taqueria. "Lose a nation, gain a restaurant," as they murmur along the corridors of the CIA. Look for a surge in Afghan eateries.

Without its overseas trading thrusts, the British would still be stuck tucking regularly into Spotted-Dick-and-custard. (No, dear bewildered reader. It is not that. It is this, a suet and dried fruit dessert.)

When the nation went marauding, along with quantities of inexcusable plunder they returned with spices and curious fruits and vegetables and the revelatory experience of food cooked in a manner that made it palatable.

Understandably, nations blessed with already seductive cuisines appear less tempted to have gone in search of better ones. Try to find an abundance of any other than Italian restaurants in Italy. Their colonial efforts were aimed at Abyssinia, today's Ethiopia. The Chinese, creators with the French of uniquely sophisticated cooking techniques, did push their dynasties outwards, gobbling up surrounding warring states and the northern part of the Korean peninsular. But aside from attempting an invasion of Japan in 1217 and their ongoing attempt to claim Taiwan as a Chinese territory, didn’t invade nations overseas.

The French are not much impressed by any food but their own. They take chauvinism to a high level, believing that in whichever region of France they come from there is no cuisine worth eating but that one. In their empire-building, their smugness caused them to miss a serious culinary revelation, ignoring the bounty of Indochina. Vietnamese restaurants are thin on the ground in France, although even in small rural towns, you will generally find a market stall serving fresh-fried "nems", Vietnamese rice-paper-wrapped spring rolls.

(Cou cou, history buffs: if you would like to contest this irresponsibly revisionist point of view with a dissertation on the far greater significance of trade, feel free to comment below.)

But in France what you will never be more than a few kilometers from is a Moroccan couscous. Morocco's national dish is the exception the French will happily tuck into. As the potent scents and vibrant hues of India twang some mystic connection and the saliva glands of Brits who haven’t even been to the country and who deplore the legacy of the Raj, so do ornately carved metal lanterns, turquoise-painted tiles and colourfully glazed terracotta pots sing to something in the soul of the French.

The good citizens of France, who would look with suspicion upon any suggestion they remove their shoes and sit cross-legged upon tatami matting for a raw fish meal of Japanese sashimi, evince no resistance to abandoning their footwear and collapsing among jewel-coloured cushions in front of a tajine, the circular dish that has given its name to the stew it cooks.

This recipe, based on the flavours of North Africa, doesn’t need a tajine to cook in. With a side dish of packet couscous that doesn’t involve the soaking, fingering and steaming necessary with the dense grain bought in Moroccan markets, it makes a winter meal that tastes of summer that can be stretched to satisfy a cast of chilled (in both senses) and hungry eaters. Keep cinnamon, coriander and saffron in your store cupboard, and you are ready for any emergency.

Serves 8

1 1/2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1 1/2 teaspoons ground turmeric

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1/2 teaspoon ground cardamom

2.275kg/5lbs lamb shanks (6–8 shanks, depending on size), trimmed

120ml olive oil/6 tablespoons, divided in 2

2 medium onions, thinly sliced

6 sprigs thyme

4 garlic cloves, crushed

3 wide strips lemon zest

2 bay leaves

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons flour

120ml/4 fl oz dry red wine

1 litre/4 cups or more chicken stock

235ml/1 cup pomegranate juice (available from Middle East supermarkets or health stores)

120ml/4floz pomegranate molasses (available from Middle East supermarkets)

slices of lemon (optional)

halves of apple (optional)

cherry tomatoes (optional)

270g/10oz walnuts

Preheat oven to 175C/350F.

Mix the first four ingredients in a small bowl. Massage into the lamb and marinate at room temperature 2-4 hours, or chill overnight.

Heat 60ml/¼ cup oil in a large pan over medium-high heat. Brown the shanks all over. Lift out and drain on paper towels. Clean the pan and heat remaining 60ml/¼ cup oil over medium heat. Add onions, season and cook, stirring occasionally, until soft and gold. Add thyme, garlic, strips of lemon zest and bay leaves and stir, about 2 minutes. Sprinkle flour over and stir until it is absorbed. Slowly add the wine while stirring. Bring to a simmer and stir until thickened. Slowly pour in stock, pomegranate juice and molasses. Simmer, stirring occasionally, about 5 minutes.

Arrange the shanks in a deep heat-proof casserole or baking dish. Push a few slices of lemon in here and there if you like halves of apples and cherry tomatoes. Pour in the onion mixture to reach three-quarters up each shank. Add more broth if necessary. Cover the casserole or dish (with foil) and bake, turning the meat occasionally, until it is almost falling off the bone, 1½ –2 hours. Remove from the oven and rest, covered, 30 minutes. Remove the shanks to a platter and tent with parchment or foil to keep warm.

Skim the fat off the braising liquid then pour it through a sieve into a saucepan and simmer over medium-high heat until reduced by a third. Add the walnuts. Return the lamb to the casserole and heat through. Season to taste. Arrange lamb on a warm platter, spoon walnuts and sauce over.

Lamb improves from being braised a day ahead then reheated. This also makes it easier to pick off the fat.

Find more newsletters with opinions and recipes here. If you want to take issue, please Comment.

Watching the British TV series "New Tricks," my wife and I were puzzled at a character's response to a visitor's suggestion that they all go out for some kebabs. The subtitles read, "Nah, we're going for some real English food, jowl frazee." We thought it might be an obscure dish like spotted dick, but a London friend set us right. He meant the Indian dish jahlfrezi, which had apparently become so ubiquitous in London that it was voted the city's favorite. This prompted me to try some the next time we visited our local Indian restaurant. It was delicious.

Having lived in California for 55 years, I've learned to love food from (literally) all over the globe. At home we make green chile chicken, chicken curry or Thai grilled chicken more often than we roast a whole bird French-style (which we also do). Food trucks around here liberally combine cuisines, rolling Korean barbecued pork into burritos, and scattering Filipino sisig over pizzas.

Leftovers from Indian dinners out find their way into what we cook for ourselves. Last night a few spoonfuls of korma dressed our pork chops. No Indian would do that, but we loved it.

It's not cultural appropriation of you don't try to sell it, right?