Spoiler alert: contains celery

A recipe for Sicilian caponata

At risk of alienating a surprisingly large number of readers of Tabled, while I could tell you all about aubergines/eggplants or Sicilian food in relation to the recipe for caponata, I’m tackling celery. It’s extraordinary how many people actively don’t like it, actually finding time to email me about the degree of their loathing.

Poor celery. It seems such an innocuous vegetable. Those watching their waistbands love it for the fact it burns more calories in the digesting of it than in the eating of it. Even so, I’ve had people rail about its dirty dishwater taste, its soapiness.

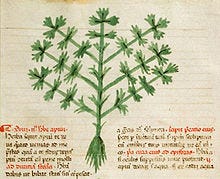

Yet its flavour provision is key to so much cooking across the world. In Europe, it’s one of the triumvirate with carrot and onion that is finely chopped to make a mirepoix or soffrito, becoming the crucial base of so many French and Mediterranean stews and soups. In Louisiana’s Creole and Cajun cuisines, celery, along with onions and bell peppers, forms the ‘holy trinity’ flavour base. In Asia, a variety with spindly stalks is used in soups and stews or pickled. Wild celery, known as smallage, is not unlike this type. Its stalks aren’t eaten raw but used to flavour soups and stews, with its leaves sometimes added to salads. It is the seeds of this plant that are sold as a spice or ground into the flavour ingredient in celery salt.

While celery grows pretty much everywhere in the world, it is a little picky, preferring salty soils and marshlands and not growing at all in Austria and increasingly rarely in Germany.

The name comes from the French céleri, which itself comes from the Italian selero, seleri being the plural of the word. (Anything Italians love enough to refer to permanently in the plural I am going to eat a lot of. One gnoccho? Doesn’t work, does it.) The Italian word came down from the Latin, of course - selinon, which was pinched unaltered from the Ancient Greek. (More evidence of the answer to the question, Who came first, the Greeks or the Romans?)

In English, the word celery is first noted in 1664, because we Angles can be slow on the uptake. John Evelyn, founding member of the Royal Society, gardener and minor government official best known as a diarist, was only able to give celery his imprimatur in 1699. Then it was officially acknowledged by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 in Species Plantarum, his classification of every species of plant then known.

Celery used to be a winter plant, important for countering the deficiencies of a winter diet that was based on preserved salted meats with few fresh vegetables. By the 19th century, celery’s season had been extended to last from the beginning of September to late in April. By the end of the same century, it was so popular in the USA that the historical menu archive at the New York Public Library shows it was the third most popular dish on New York City menus of the day behind coffee and tea and cost more than caviar.

Celery has come a long, long way. Its leaves and flower clusters formed part of the garlands found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, who died in 1323 BC. Seeds dating to 7 BC were discovered in the Heraion of Samos, the sanctuary to the goddess Hera, though in neither case was it clear whether these were wild or cultivated, celery cultivation apparently having begun aeons ago. Homer’s Iliad mentions the Myrmidons’ horses grazing on the wild celery of the marshes of Troy and in his Odyssey writes of fields of wild celery and violet surrounding Calypso’s cave. (I just want celery-haters to know that the plant goes way beyond being a green gutter to fill with crunchy peanut butter.)

Homer’s celery would probably be unrecognisable to us now. The plant was submitted to long years of seed selection to give us the crisp celery of today. Like so many other plants and flowers, it has become cultivated for year-round availability. Originally, its seedlings were transplanted into deep trenches and the plants earthed up as they grew, to blanch their stalks. To by-pass that outmoded activity, further intricate development has occurred, resulting in the creation of self-blanching varieties. Isn’t celery clever.

I fully appreciate that as with fresh coriander/cilantro, anyone who loathes it can spot it at first taste. But just in case you want to give it another test, here is a recipe where it’s the aubergine/eggplant that stars, not the celery. Its role is only a supporting one and I suppose if you like the recipe but not the ingredient, you might use fennel instead. Or leave it out.

100ml/5¾ fluid oz olive oil

3 large aubergines/eggplant cut into 2cm/1 inch cubes

2 large shallots, peeled and chopped

4 large plum tomatoes, roughly chopped

2 teaspoons capers

50g/1¾ ounces raisins

4 celery sticks, sliced

50m/3⅓ red wine vinegar

handful toasted pine nuts, and basil leaves, torn

Pour the olive oil into a large saucepan over a medium heat and add the aubergines. Saute, stirring regularly, 15-20 minutes until soft. With a slotted spoon, scoop the aubergines out of the pan. If necessary add a little more oil then the shallots and cook for about 5 minutes until soft. Add the tomatoes and cook slowly till they become soft and slumpy, then return the aubergines to the pan. Add the capers, raisins, celery and vinegar, season well and cover with a lid. Cook over a low heat for 40 minutes until everything has softened. Stir gently once or twice.

Scatter over the basil leaves and pine nuts and serve with slices of warm crusty baguette.