It’s less “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire” that herald Christmas for me than chestnuts roasting in glowing braziers along Oxford and other Streets of London. There’s something very specific about their smell, in the same way the smell of barbecues evokes pleasures of a very particular kind. Growing up, that sweet smokiness was a regular part of Christmas. My mother had unearthed a proper chestnut roaster in an antique shop for a few shillings. It was a brass square lidded affair into which we dropped the chestnuts, lightly scored to prevent them bursting, to set onto the embers of the sitting-room blaze, shaking it every so often.

As soon as their skins blackened, the chestnuts were decanted onto the hearth to cool a moment before we set to with tingling fingerpads to shell them while still hot.

When I lived in the US, it was one of the tragedies of Christmas that chestnuts weren’t readily available. While American chestnut trees (Castanea dentata and C pumila) had grown in the north of the United States, and Native Americans were known to have eaten chestnuts long before colonists arrived with their own, different, stocks, they were almost completely wiped out in the early 1900s by a blight introduced in trees imported from Asia (Castanea mollissima). In 40 years, nearly 4 billion died. Given a quarter of hardwood trees foresting the Appalachian Mountains were chestnut, and most wood-frame houses and barns east of the Mississippi River were made from chestnut wood, the blight had a devastating effect - on the economy as much as the landscape.

Today, even after huge efforts to repopulate them that began in the 1930s, only a few original clumps survive, in Michigan, Wisconsin, California, and the Pacific Northwest. Genetic material has been harvested from them to engineer a disease-immune American chestnut tree. The blight-free trees that now exist are the Dunstan chestnut, developed in the 1950s in Greensboro, NC.

Chestnuts have been a staple across southern Europe, Turkey, and southwestern and eastern Asia at least since 2000 BC. To early Christians, chestnuts symbolised fertility, chastity, honesty, and hidden virtue. (Wouldn’t you have liked to have been a fly on the wall at the synod conference where that link was agreed?) They were grown to stand in for cereals in areas where those did not grow well - or at all. When they weren’t slaughtering the enemy, the Romans planted chestnut trees across Europe on their various campaigns. The Greek army survived its retreat from Asia Minor in 401-399 BC thanks to their store of chestnuts. Discorides, said to be the father of Pharmacognosy (the study of drugs obtained from plants, animals and fungi) who lived from 40-90 AD, and later the better-known Galen, 129-216 AD, Greek and Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher, both noted the chestnut’s medicinal properties (high in fibre, a source of antioxidants, as well as, possibly, acting to support heart, blood sugar, and weight management) - along with its capacity for inducing flatulence when too many are eaten.

Until potatoes arrived from South America in the mid-1500s, chestnuts were the prime source of carbohydrates for many communities across Europe. Ground down, dried chestnuts are turned into flour. During the Second World War, bread throughout southwest France where chestnut trees are prolific was made from chestnut flour. Chestnut loaves are still sold today across the Dordogne. I don’t recommend them except for their curiosity value - though they would make useful doorstops. Traditionally, trofie, the pasta served with pesto in Liguria, are made from farina di castagna - chestnut flour.

Confuse sweet chestnuts with horse chestnuts at your stomach’s peril. The latter should only be used for threading onto strings to play conkers, the game whose aim is to smash the opponent’s conker to smithereens.

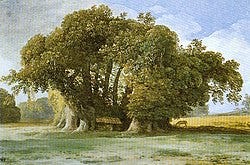

Horse chestnut trees have a studier ability to survive than the sweet chestnut. The Castagno dei Cento Cavalli, the Hundred-Horse Chestnut growing on the eastern slope of Mount Etna in Sicily, is the largest known chestnut tree in the world, with a circumference of 57.9m/190ft, and the oldest, between 2000 and 4000 years.

In 1720, the circumference of the Tortworth Chestnut in the English county of Gloucestershire, noted in boundary records compiled in the reign of King John (1199-1216), measured over 15m/50ft.

The impressive age of horse chestnut trees is reflected in the classic response to a stale tale, joke or anecdote, “That’s a hoary chestnut!”, with ‘hoary’ an old English word referring to anything old or whitened with age. In the wild, you can tell the difference between the two chestnuts: in spring, sweet chestnut trees flower with drooping pale yellow catkins, while horse chestnuts bear white, red or rose ‘candles’.

In autumn, horse chestnuts develop a thick bright green shell with few stiff spikes.

Sweet chestnuts have softer prickles as densely packed as a hedgehog’s armour.

Now is the season for sweet chestnuts. Even if you can’t buy them fresh, this excellent soup can be well made from tinned or frozen or vacuum-packed chestnuts so long as they haven’t been sweetened. If you are using chestnuts from scratch to simmer and peel, you would benefit from this little knife

I was brought from a pound shop in Japan. But so long as you keep the chestnuts in their hot water while you tackle each one to prevent their two skins from drying out again, a small kitchen knife works. Be careful with its tip.

My recipe calls for you to melt the onions and celery (optional, you celery-haters) in the fat of the bacon you fry to a crisp to crumble over each soup before serving. I often prefer a swirl of cream to bacon crumbs, so use goose fat instead. Butter or oil will also do. Some call this Franciscan soup, saying it was first made at the monastery of La Verna, where St Francis received the stigmata. From high up there, the monks look down over the Casentino valley, ringed by chestnut forests.

500g/1lb chestnuts

115g/4 oz thinly cut streaky bacon

170g/6 oz chopped onion

55g/2 oz chopped celery

1.15 litres/2 pints light stock

235ml/½ pint single/table cream or whole milk

salt and ground white pepper

Score the chestnuts round their middles. Boil for 15 minutes, take off heat, allow to cool only enough to handle them and remove both skins while keeping the chestnuts submerged. If they cool, the skins won’t come off. Just bring them back to the boil if that happens.

Fry the bacon in a large sauce pan till crisp then remove to a paper towel to cool. When cool, crumble into small pieces and set into a small bowl. Over medium-low heat, fry the onion and celery in the bacon fat till softened, add the chestnuts and the stock and simmer till the chestnuts are soft, about 30 minutes. Season to taste with the salt and ground white pepper, Blitz to a puree and pour through a sieve into a clean pan. Add the cream or milk and reheat.

Serve either with a swirl of cream or a sprinkle over or pass the bacon crumbs.

My olfactory memory cells are jumping for joy. In my 20s I lived on Chestnut Street in Boston with an illustrious group of international students most from Europe in a house reminiscent of a British row house with the kitchen open to the back on the ground floor. Having lived in London just before taking up residence; the kitchen was especially important to me as was the owner who cooked for us but also provided me with the chance to cook on a massive six burner gas stove for my hungry jazz musician roommates. Thank you for this culinary meander as it also brings me back to university days in Lyon, France and my first visit to Paris where I discovered that history could be told thru art, food, fashion etc. PS there was a Chestnut tree at the top of my street growing up and we played conkers too. Cheers to you and yours.

Thank you for restacking!