Find more newsletters with opinions and recipes here. If you want to take issue, please Comment.

The public river boat from Chang Rai in Thailand takes two days to putter down the Mekong to Luang Prabang in Laos. The jungle claws downwards from the distant mountain summits, all the way to the cappuccino waters of the wide river. Only tracks trampled ochre by swaying elephants shouldering logs, herded along the river bank by young torso-bare boys with switches tamed the wilderness.

As the globe of tangerine sun rolled down the sky, we drew for the night into Pak Beng, a small settlement clinging to the slope above the Mekong. The village has benefitted only recently from the completion of a hydroelectric station downriver.

Back then, it was dependent on generators for electricity. The ferry captain advised passengers to get up to the village with all speed and find somewhere to eat before they were switched off and the village plunged into darkness.

The orchestration of rural Laos is a judder of generators. In Pak Beng, they pummelled the eardrums, a battalion of road-bores drilling in unison under a sequined ceiling of silent stars. I wandered randomly off the mud-baked road into Hasan’s. Out of the gloom came a jovial London voice. ‘Hiya! You want something to eat?’ Hasan had been brought up 6000 miles from any jungle - in Ealing, 8 miles west of the Houses of Parliament. His father had been an importer focusing on Laos, a less explored part of South East Asia. Once Hasan left school, he accompanied him on trips. Hasan was hooked. Life in Pak Beng, he decided, offered opportunities. He’d been there long enough he no longer heard the generators.

Days later, at the end of a lengthy bus ride from Luang Prabang that wound through the tribal mountain villages east of Vientiane past roadside food markets selling dog, another generator split the silence. Pulling at dusk into Tha Bak, a tiny outpost above the Namkading River, the community generator rumbled into action. For a few Lao kip, an old Hmong woman offered a corner of her house-on-stilts to lay down a sleeping bag. In the river below the hut, elegant metal fishing boats were moored, slender tubes fashioned from fuel tanks dumped by US fighter planes during the war returning to base from bombing sorties.

In a sudden downpour, grandmother squelched off in flip-flops along the red mud lane towards the family’s rice store for next day’s supplies of sticky rice, to soak overnight. A group of men passed by, striding up from the river below the village where they had gone fishing, unsuccessfully it appeared from their buckets. The water was too low. She returned with her apron hanging like an udder, filled with rice.

Every Hmong hill tribe family has a rice store, a hut of woven bamboo strips set on stilts along the bank high above the river. Laotians’ rice consumption is among the highest in the world, around 206kg/454lbs a year per capita.

Over 60% of the country’s arable land is used for its cultivation. But with such mountainous terrain, land that is farm-able accounts for only 4% of its total area. That’s the smallest amount of arable land of any Southeast Asian nation. Needing regular and generous irrigation, rice is produced predominantly in the country’s lowland along the Mekong and other rivers.

Glutinous rice is Lao’s most popular. It takes longer to digest than other varieties - important in a country with high rates of undernourishment.

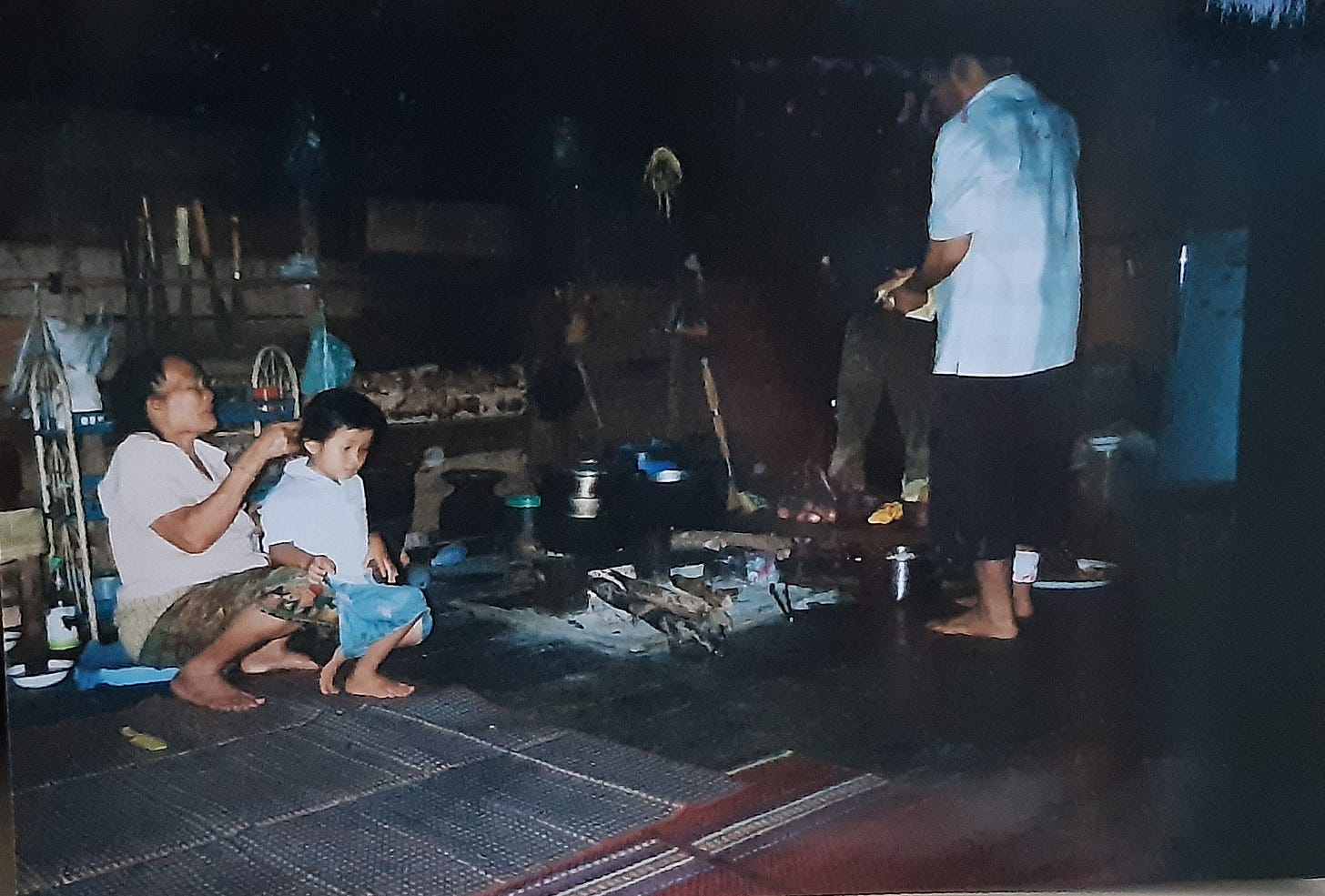

In the kitchen, a space on the open verandah defined by a small stone charcoal-fired brazier and pots and pans hanging from wall struts, grandmother squatted among the toddlers the younger women of the household had unpeeled from the cloth around their waists and set upon the floor. A chicken that had been strutting through the house was reduced to chunks with a few well-judged swipes of a cleaver.

Mayflies swarmed suddenly, in a cloud two feet deep around the single strip light, dropping into clothes and hair. The family clapped in delight. Someone rushed from the kitchen bearing a wide bowl of water. As the mayflies tired, they flopped into it, swam frantically, then drowned.

Once the water had disappeared under a carpet of floundering insects, the family took it in turns to draw their hands slowly across its surface. When they pulled them away, mayfly wings were fixed to their palms. They scraped them off and fed them to the gleeful chickens. The mayfly bodies were stir-fried with garlic - and fed to the adults.

They guzzled them with equal glee. Mayflies are a delicacy that comes free, their season so brief they may only provide one bowlful a year.

While rice doesn’t qualify as a delicacy, it does qualify as a precious commodity. Weather conditions in Lao have been dreadful over the past few years, to the detriment of rice crops.

What it seems to have weathered so far is Covid-19. With a population of just over 7 million, the country has been fortunate. In the year up to mid-April, Laos has had no deaths, with only 247 cases reported. 137,026 vaccines have been administered.

But it’s a country dependent on tourism and Covid-19 has closed its borders with China and Thailand, prime sources of its tourists. Migrant workers to neighbouring countries have had to return home, meaning the end to remittances in US dollars - $125 million in 2020, according to the World Bank.

Eventually, the borders will open again. But Laos, like every nation watching the tragedy escalating in India, is not just at the mercy of a virus. It is also at the mercy of its neighbour to the north.

In China, eleven massive dams straddle the Mekong, a building project begun in the 1990s. They’re of concern to the nations fed by the mighty river - Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. If the Chinese want to parch these countries of water, the dams provide them with the means.

Some years ago, the centuries-old 3-day Lao New Year Water Festival in Luang Prabang had to be cancelled, for the first time ever. There wasn’t enough water - to wash the images of Buddha, to splash, and to pour over the hands and head of devotees in blessing. Last year along the Thai-Laos border, the Mekong riverbed and shoals became exposed. Isolated pools of flopping fish were unable to reach their spawning grounds.

The Tonlé Sap, a freshwater lake attached to the Mekong in southern Cambodia of vital importance to Cambodia’s food supply, is in dangerous decline. Over six months in 2019, China’s dams blocked from entering the lower Mekong a quantity of water so large that there was no habitual monsoon-driven rise in water levels over the Thai border.

Everyone needs water, but the people of Laos don’t just need it for their fish. They need it for their rice. What purpose China would gain by holding Laos and its neighbours hostage to water and creating a potential food crisis is a puzzle. If Laos adds a struggle with water shortages to its other deprivations, it’s hard to see how its people will survive.

This rice is soothingly delicious with everything from stir-fried vegetables to soy-poached chicken, ginger-steamed fish - or with nothing but spoonfuls of equal quantities of scallions and fresh peeled ginger chopped together very finely and bound with a little sesame oil.

Serves 4

185g/6 ½ oz/1 cup sticky or glutinous rice

½ tin unsweetened coconut milk

160ml/5½ fl.oz/⅔ cup water

½ teaspoon salt

Rinse the rice in several changes of water until the water runs clear. Add the coconut milk, water and salt to a small pan. Add the rice and bring to the boil. Cover, reduce heat to lowest and allow to steam for 20 minutes. Remove cover, fluff rice with a fork and serve immediately.

Beautifully written, and painfully sad. We found the people of Laos warm and welcoming. But I wonder how the Chinese will parse the competing demands of their dams on the Mekong and the high-speed train they’re planning to bisect the whole peninsula. (See https://www.voanews.com/east-asia-pacific/laos-braces-promise-peril-chinas-high-speed-railway)

I was drawn in so quickly by this beautiful writing, Julia. Gorgeous and consequential.