Food as entertainment not education. Who cooks?

A recipe for Red wine-braised duck legs with redcurrant or quince jelly

As the writer of three cookbooks, there are times I wonder who their readers are. I have a library of mostly battered cookbooks some 50 strong, mercilessly whittled down from several hundred. Those themselves were of necessity culled monthly in the days when, as a Food Writer for a global news agency, I was sent books almost daily, delivered by the long-suffering mailman staggering up the steps under their weight.

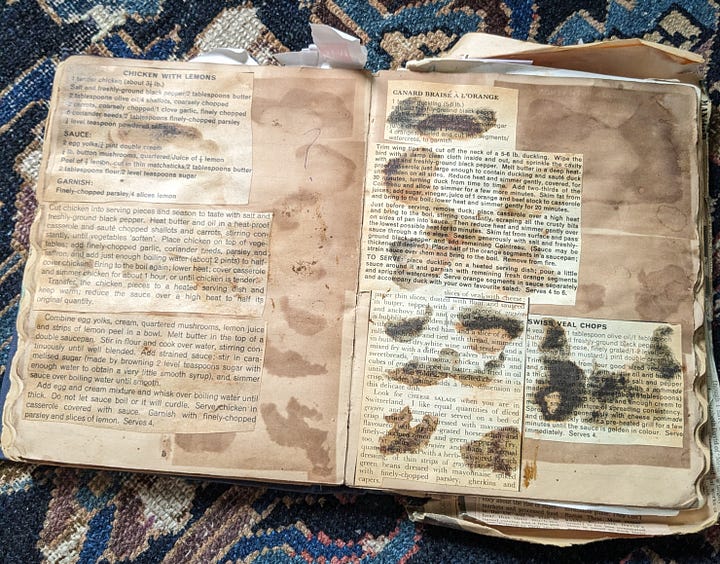

My mother, a remarkable cook, taught herself solely from Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food and never really did more than flick through the few other cookbooks she was then given. What she also had was a scrapbook of recipes clipped from newspapers with the scribbles of recipes dictated by friends.

These days, I more often access Google for a recipe than I do a book. I suspect most people new to cooking and excited by the prospect of tackling a novel dish head to YouTube not to bookshelves. The cookbooks they’ve bought may lie on the floor by the bed to ring the changes in bedtime reading.

They are missing out. Social platform cooking vids are limited by audience attention span, so leave no time to cover context or technique. On Instagram or Tiktok, you won’t learn the history or social circumstances that were the background to creating whatever it is influencers are cooking. Of course, it may not matter: for the inquisitive there are cookbooks that do more than just provide the instructions for creating a dish, and specialist tomes on specific food subjects.

For decades, cooking has been a means for TV companies to make a handsome profit on mainstream entertainment with little outlay because cooking shows are so cheap to produce. Now self-filming in the kitchen has become a route to creating social media stars (who may, ironically, aspire to turn their 60 seconds at a stove into a physical cookbook). So how do we expect to preserve and record the traditional recipes of our grandparents and their grandparents? Novice cooks sign up for a delivery of packaged portions that are turned into a meal by following the step-by-step instructions that come with them. But are they hassling their elders for the secrets of their traditional food? And will their ancestors be confident that there’s much point in passing them down to a generation whose approach to eating and cooking is so different from their own?

The concern that we may be losing what is called our culinary heritage is official. UNESCO has taken steps to formally recognise several national cuisines and cooking methods - French gastronomy, Mexican food, Washoku (traditional Japanese cooking), Ukrainian borscht, Singapore’s hawker street food culture, the pizzaiuolo’s art of making the authentic Napolitan pizza. That’s just six out of a modest total of thirty global culinary traditions and practices on its ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ list compiled in 2013.

When I lived in Greece, I was astonished to be introduced to dishes I had never experienced in the Greek restaurants of London whose menus stick to taramasalata, roast lamb, grilled fish, and tomato-onion-and-cucumber salad but little more. It may have been a consequence of the village’s distance from any major city or the restrictions of a tight budget, but the women baked pies made from wild plants they culled from the mountainside, snails they collected and fried in their shells so they popped when cooked, stews with parts of an animal that back in the UK would have been consigned to the bin, dried fish that was reconstituted with tomatoes and potatoes, made sauces from stale bread or garlic or with finely chopped hot peppers beaten with oil into yogurt, and salads of pickled caper leaves. If I ate a moussaka, or a stuffed pepper or a souvlaki, it was because I had made it myself.

Big Food Biz globally has transformed food production processes. It has altered what we buy and how we eat. Its creation of an extraordinarily wide range of prepared meals, easy and speedy for time-strapped families to put on the table, has led to a homogenisation of diets and dishes. Along with this has come the loss of food traditions and practices, of preparation techniques. In addition, post-COVID food safety fears have put additional pressure on increasingly stringent standards for food hygiene. The result is that the developed world is losing its culinary heritage. At the same time, the swell of tourists discovering parts of the globe only previously visited by travellers on handsome budgets is reducing the range of local dishes available to them as restaurants focus on a small selection of recipes quick to serve and guaranteed to please.

Once upon a time in the west, food was part of our identity. While the Brits still tuck into fish and chips, and roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, and the US into burgers and fries, hot dogs and ribs, a significant part of the developed world’s eating week is taken up with Chinese take-outs, Korean fried chicken, bao buns, Indian curries, Mexican tacos, and more. These are not meals we tend to make in our own kitchens. We’re not cooking much, just forking in take-out feasts while glued to cooking shows.

Food vloggers do pass on traditional recipes, particularly those in Asia. But they’re limited. One, a hot oil+scallions+garlic+chillies+ginger dipping sauce, is commonly demonstrated by every one of them. It makes sense: they can be demonstrated inside a minute and besides we’re all in love with gyozas, dumplings, and dipping all manner of food in sauce. What we see less of are the recipes that belong to parts of Asia and the rest of the world whose menus haven’t yet penetrated the mainstream, so we remain unfamiliar with them. There is a danger these may disappear from record before we become so, and even from within home kitchens where the transmission by word or example of the techniques, traditions and recipes surrounding food is disappearing as different generations no longer live together in tight communities.

Just as we have seed banks to preserve the continuity of plants, edible and floral - over 1700 of them around the world - so, perhaps, we should create recipe vaults, to prevent recipes from disappearing before the newest generation of eaters has learned how to cook.

A classic French duck dish that is less familiar than Duck à l'orange or magret of duck is this recipe using the legs, whose elegance belies its simplicity of execution.

Serves 4

4 fresh duck legs (available on the internet)

½ teaspoon five-spice powder

rosemary leaves from a bunch of sprigs, about 4 tablespoons

4 fat garlic cloves

half bottle red wine

240ml/8¾ fl oz chicken stock

2 tablespoons redcurrant or quince jelly

Preheat oven 190C/375F.

Chop the rosemary and garlic in a blender and rub it on the meaty side of the duck legs. Place legs in one layer in a roasting tin and sprinkle with salt and five spice powder, and let marinade for at least an hour.

Roast in the oven for one hour. Remove all the fat and then add the stock and half a glass of the red wine to the tin. Return to the oven, lower the heat to 175C/345F and roast a further 30 minutes, or until the stock has evaporated. If it hasn’t, drain it off.

Heat the remaining wine and jelly together to a gentle simmer, stirring until the jelly has melted. Pour the jelly/wine over the duck and return to the oven. Raise the heat to 190C/375F again and roast for 20 minutes or until wine is reduced by half. If it hasn’t, move the legs to a warm plate and boil the wine down fast in a saucepan on the stove top. Serve at once.

Last time I reorganised my kitchen cupboards I decided to sort ingredients by cuisine, rather than type. My first go involved splitting into Japanese, Chinese, Korean, SE Asian, Mexican, and "white people food", but when the last pile turned out to be just popcorn kernels and a solitary tin of cannelini beans I reallocated that shelf to my collection of dried chillies. 🤭

If, like me, you don't really enjoy eating meat, traditional British cuisine doesn't have anything to offer except puddings. French food is grim, overwrought and drowning in sauce. Italian food is magical until you ask them to cook a vegetable. Central and Eastern European food is just stodge with extra stodge. Spanish and Greek both are great in their own ways, but a big chunk of that comes from their locations and histories.

I'm becoming more and more interested in West African food (Ghana, Nigeria, The Gambia especially), but so far I've only enjoyed those in restaurants. I want to try making domoda, a Gambian peanut butter stew that doesn't look like an impossible place to start. ('pologies for the essay)

Hear, hear! A recipe is a moment frozen in time -- of the author, of the cuisine, of the history of the dish, of the cook who recreates it. It is story telling of all five senses. It is how we connect with the past + with the future. Thank you, Julia!