When I reached the age that my classmates and I would roll up our school skirts to just about cover our bums and haul our black gym socks up over our knees, a bunch of us would skip going straight home and head instead for the Wimpy Bar not far from school. I can’t call them My Team, My Crew, My…what?? - I was never popular enough to be anything more than an apprehensive hanger-on.

I’d cram against them into the red Formica-topped tables and munch on a Wimpy and fries with Lesley, my best friend who didn’t much like me, weighing who Roger with the cool quiff fancied more - her or me. Her, definitely. She’d climb out of her bedroom window to Roger waiting in the street below and scamper off to parties with him, home at dawn. I don’t suppose he even knew in which zone I lived.

That Wimpy Bar, like Starbucks today, was one of hundreds on nearly every British high street. In London now, only three remain. Founded in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1934, and reaching a mere 26 US sites at its peak, it faded to only seven by 1977 and today no longer exists. In the UK, it was subsumed into the Burger King brand, that big bouncy burger which, in its Wimpy days, was only a flat disc of meat peeled off a sheet of paper and tossed onto the griddle.

The Wimpy as they were called, never a ‘burger’, was, in its way, a patty ahead of its time. Walking down Soho’s main street a few nights ago, the lines outside Junk Smash Burgers stretched around the corner.

Two weird bits of information: First, Junk is a French company. Yes, that nation which rails so loudly against anything American, in particular its fast food. Yet the chain has outlets in France from Paris to Bordeaux, Lille and Lyons and more. There are buttons on its web site which allow you to switch between the UK or the French version at will. Second, Junk’s burgers are as flat as a Wimpy. If you want a fat Junk burger, you must order an XXL, which is five, yes five, of Junk’s slender meat discs slammed together. Burgers so big you crack your jaw trying open it wide enough to bite into them are beyond being passé.

No question you’re familiar with the smashed cucumbers that became a social media and home cooks sensation, their sesame dressing clinging so well to the multiple surfaces of the lightly crushed cucurbits. You may be aware that even parsnips and peas are being fashionably squished to a lumpy, baby-pleasing and digestible pulp and taking over from avocados on toast; and that whacked potatoes are replacing pastry in muffin and quiche pans to create uber-hip and photogenic casings for traditional fillings. They each make for seductive easy-peasy, you-can-do-this-too Instagram challenges. But in case you aren’t familiar with the smash burger, it’s a ground meat disc smushed flat by a spatula into a hot griddle to create a thin Wimpy-style patty but with a crispy crust which a Wimpy never achieved. Ever. The Wimpy was grey.

What smashing does to a burger is to provoke what’s known as the Maillard reaction. This is the chemical reaction between amino acids and ‘reducing sugars’ (monosaccharides we don’t need to go into) that creates the compounds which give foods that have been seared and browned their intense flavour. Think of crusty bread, of toasted marshmallows, of fried onions - you get the picture.

The benefits are not just visual and delicious. In the creation of a burger they allow for much cheaper cuts of meat to be employed. The high fat, high quality beef of a monster burger can be abandoned in favour of a less expensive ground meat which, when smashed, can absorb seasonings and marinade flavours far better, as well as cooking the patty consistently across its surface.

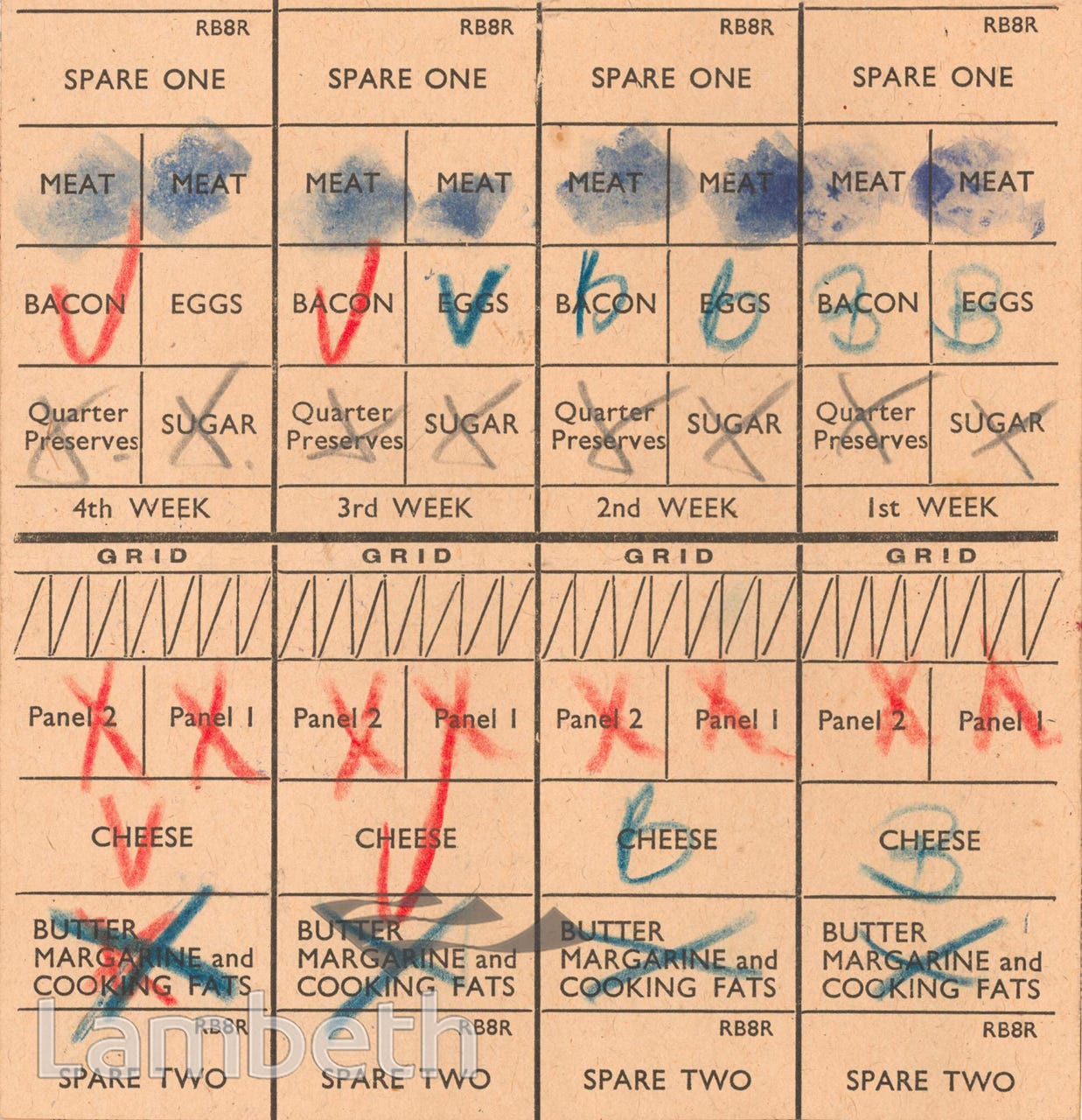

Buying cheaper cuts is not just an economical consideration. It encourages better use of animal parts that get short shrift, and are often discarded. As populations grow and climate changes bite, governments are beginning to whisper (this is an early alert you seriously should attend to) about food rationing. Yes, that food distribution control last experienced in the developed Western world during the Second World War and in Britain for nine years after the end of it, with paper booklets to record what you received and what you were permitted to receive from a limited selection of foods courtesy of the Ministry of Food.

James Pomeroy, global economist of HSBC, predicts a population increase of another 800 million in the next 20 years, putting pressure on food supply and demand.

The proposal of rationing is being tested. And consumers aren’t altogether against the idea. A survey by Sweden’s Uppsala University found 40 percent of people across the five study countries, the USA, Germany, South Africa, Brazil, and India, support it for high climate-impact goods such as meat. It won’t surprise you to know that the two most powerful economies, the USA and Germany, had the lowest acceptance levels. But not by much.

It’s the same old story: there is enough food in the world for everyone to eat. But not everyone is getting equal access to it. Plus, the expanding global population is becoming wealthier. Richer consumers eat more, and demand more luxury food like meat and dairy that is expensive in resources to produce.

Turning for a solution away from meat towards fish comes with its own problems, created by intensive fish farming to combat over-fishing. Last month, it was revealed that during the 18-month production cycle it takes to raise salmon in seawater, over one million fish had died in one of the UK’s largest suppliers. They came from two neighbouring farms under the auspices of Mowi Scotland in Loch Seaforth on Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. This despite the farms being certified for supermarket sale by a respected not-for-profit. This video is disturbing: https://animalequality.org.uk/news/salmon-suffocating/

Mass deaths of farmed salmon, in some cases an indicator of poor welfare, or increased sea temperatures, or both, are a growing problem, according to Scotland’s Coastal Communities Network, protector of the country’s coastal and marine environments. “We expect to see more salmon deaths in Scotland because farms are becoming even larger,” said John Aitchinson, on behalf of CCN’s 30 member groups.

After tuna, salmon is the UK’s most popular fish, with sales worth £1.3 million. In the States, it’s the most popular after shrimp, with sales of US$ 1,430.2 million. In southern Chile, source of nearly half of salmon sold in the US, increased sea temperatures are are only part of the challenge fish farms face. Over two-thirds of Chilean farmed salmon is rated red by Seafood Watch due to the high use of antibiotics. A red rating means an aquaculture operation is considered unsustainable and a high risk to the environment or marine life. Fish farm sizes globally are growing to cope with consumer demand. Perhaps we should expect less farmed salmon and buy more of the less familiar but equally delicious fish.

So far, monkfish is wild-caught, sustainable, and healthy, though it can be supplied by greedy bottom-trawling factory ships whose catch you should try to avoid.

This recipe puts you right in the fashion zone by pairing it with crushed (almost like smacked) potatoes.

Serves 4

2 x 350g/12 ½ oz cleaned monkfish fillets (cod loin can substitute)

750g /1 ¾ lb waxy potatoes like Yukon Gold or Ratte, scrubbed but unpeeled

2 tablespoons fresh parsley leaves, roughly chopped

1 tablespoon fresh basil leaves, roughly chopped

4 fresh sage leaves, roughly chopped

2 anchovy fillets, drained and chopped

1 tablespoon capers, drained and chopped

1 small clove garlic, peeled and finely chopped

1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

Zest of 1 lemon and 1½ tablespoons juice of 1 lemon

2 tablespoons plus 5 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 oz/50g rocket arugula leaves

Flakes of sea-salt and freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven to 180C/350F.

Season the monkfish with salt and pepper and set aside. Boil the potatoes in salted water until tender.

In a blender, blitz together the parsley, basil, sage, anchovies, capers, mustard, lemon zest and juice, and vegetable oil to make a puree and set aside.

Heat 2 tablespoons of olive oil in a large ovenproof frying-pan. Dry the monkfish and sear quickly over medium-high heat to brown all over. Move the pan to the oven and roast the fish for 10 minutes until firm but still moist in the middle. Wearing oven gloves remove the pan from the oven, cover to keep warm, and set aside for 5 minutes.

Drain the potatoes and return them to the pan. Crush each potato against the side of the pan with the back of a fork until it just bursts open. Pour over the remaining 5 tablespoons olive oil. Spoon them onto a warmed platter leaving a bare edge of 2-3 in/5-7cm, sprinkle with sea salt flakes, and grind pepper over. Distribute the arugula/rocket around the bare edge of the platter. Drizzle any pan juices over the potatoes. Cut the monkfish fillets at a 30 degrees angle into thick slices and lay them on top of the potatoes. Whisk the herb sauce to amalgamate, and dollop some over the fish then pass the rest in a bowl.

The most recent episode of the Food Program is well worth a listen. It was all about the fishing industry in the UK.

Five seafood species make up 80% of what is consumed in the UK – while at the same time the vast majority of what is caught in UK waters gets exported. But is that trend beginning to shift?

In this episode, Sheila Dillon hears how initiatives like the "Plymouth Fishfinger" are hoping to make more use of fish that has often been seen as ‘by-catch’, and how seafood festivals are working to connect the public with local seafood, and can even help regenerate coastal communities.

She also hears how the Fish in Schools Hero programme is working to get young people to try more seafood, and shows how simple it can be to prepare.

Also featured are Ashley Mullenger (@thefemalefisherman) and tv chef and campaigner Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/food/programmes/m0024p2q

I love monkfish! I order it any time we’re in Europe and I see it on the menu because I never see it at home. Why is it so rare in the United States? (By the way, do take you smashed potatoes up a couple,notches with chicken or duck fat)