I scream for frozen vanilla

A recipe for Crème Anglaise and Crème brûlée

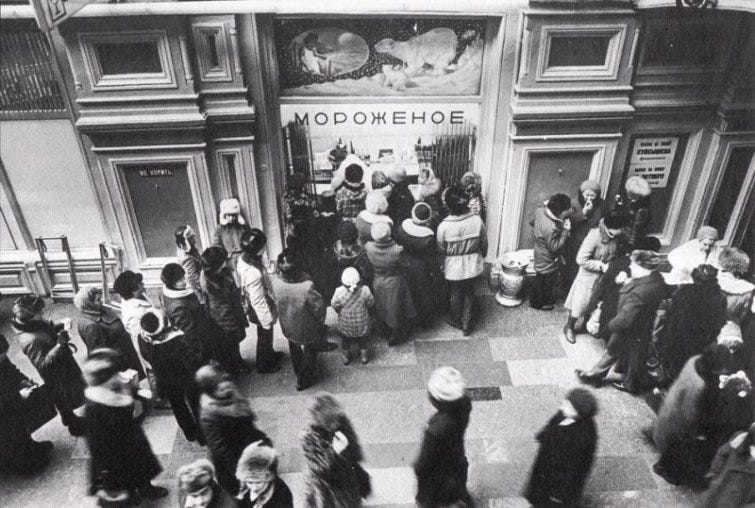

I can’t resist ice cream. I don’t actually like it all that much , but it’s such a symbol of self-indulgence and of summer - albeit that when living in Moscow, we would line up in Gorky Park in winter between the snow drifts in a long queue for marozhona from carts on wheels.

Gorky Park is the recreational equivalent of the pig: not a piece of it goes to waste. It came into its own in winter, water poured along the paths to a create long and winding and very bumpy ice rink through the trees. Martial music blared from the overhanging branches.

A stakanchik was a cup-shaped wafer filled with ice cream, generally vanilla, chocolate if you were lucky but that was rare, or a berry flavour. There was also a lakomka, vanilla ice cream bound in a coat of frozen chocolate cream, a melting mess to eat even in below-freezing temperatures.

Ice cream came in several different types. GOST, the Soviet department that set the standards for all food production, stipulated that slivochnoye (cream) ice cream had to be made with cream as well as milk. Molochnoye (milk) ice cream was produced with low fat milk, while the rare plombir was made from full cream and egg yolks.

Then we moved to the United States and discovered Baskins Robbins and Dayvilles, with their 36 different flavours.

Still, vanilla has always been my favourite. It sets the gold standard: if you can’t make a good vanilla ice cream (and a good one is a very rare find), then you won’t make a brilliant any other flavour.

Pure vanilla may seem an uncomplicated ingredient. But because vanilla beans are so expensive, short cuts are made. They are replaced with man-made Vanilla Extract (if you’re lucky) and Essence of Vanilla if you’re not. Essence or Aroma of Vanilla - commonly used in otherwise food-conscious France - should be banned products. Nothing and no amount of technique or cream can disguise their ersatz taste.

The vanilla bean or pod, which shrivels and darkens shortly after being picked, comes from a variety of orchid originating predominantly in Mexico, and now growing there and in Madagascar and other islands in the Indian Ocean. Among the first people to cultivate it, around 1185 or earlier, were the Totonacs who lived along the east coast of Mexico. They used it as a fragrance in temple ceremonies and as a good luck charm in amulets, as well as a flavouring for food and their chocolate drink.

Second only to saffron in expense, the price of vanilla is high because of its production costs. Harvesting can take up to eight months, the curing and drying a further nine. It needs pollination to produce its pods which it seems shy to engage in without help. But in 1841, Edmond Albius, a 12 year-old slave on the French island of Réunion, to which, in 1819, French entrepreneurs had shipped the bean from Mexico, discovered the plant could be pollinated quickly by hand. It was a hugely and expensively intensive job. Nevertheless, widespread cultivation began.

Investigations into how to reduce the curing process without reducing the intensity of flavour of the bean or pod are currently taking place, but so far without 100 percent success. The vanilla bean contains the key compound vanillin. But it’s a flavour whose complexity can’t be vibrantly reproduced with lab-made vanillin, as a tasting of ‘Essence’ or ‘Aroma’ will confirm.

Scientists are working on vanilla extracts from beans sourced from different countries, curing them using different techniques. While they have managed to identify 20 main compounds, they haven’t yet pinpointed other ones crucial to vanilla’s overall complexity of flavour.

The researchers haven’t given up. Their findings, said Dr Diana Forero-Arcila of Ohio State University at the American Chemical Society’s recent Fall 2022 conference, will be applicable to the food and agricultural industries. “This information will give tools to the whole vanilla supply chain from farmers to industries, which can include strategies for breeding and curing processes as well as improving the formulation of products to compete with high quality vanilla goods and secure consumer liking and acceptance.”

From the last part of that determination, I’d guess they’re not willing to take your No Thanks for an answer. “The more you understand about how to make the materials more valuable, the more that value should flow through the whole system,” said Dr Devin Petersen, principal research investigator. This sounds a bit like what citizens of the UK, the US and beyond would recognize as our current politicians’ insistence the ‘trickle down effect’ of tax breaks for the rich will enrich the less well off.

One of the best ways to appreciate vanilla is in custard - not that just-add-milk yellow powder the Brits are familiar with, but Crème Anglaise. Frozen, it becomes the best vanilla ice cream. As is, it improves any dessert it is poured over. It has an unfair reputation of being a volatile creation. It really isn’t if you take it slowly. I’m also including Barbara Kafka’s excellent microwave recipe which uses vanilla extract and makes it incredibly quickly and easily. It’s the best justification for buying one of those machines, generally unnecessary if you like to cook.

Both mixtures, cooled, make Crème Brûlée. Simply pour into 4 ramekins or one shallow dish and refrigerate overnight. The following day, sieve over 3-4 tablespoons of sugar and caramelise it with a blowtorch or, carefully watching, by setting it at least 10cms/4ins away from a hot grill/broiler.

470g/1 scant US pint double/heavy cream (A UK pint is just over 19 fl oz, a US pint is 16.65 fl oz)

1 vanilla bean, split

4 large egg yolks (save the whites for a meringue)

2 tablespoons sugar

Scrape the seeds from a quarter of the bean with the point of a knife into a small saucepan. Stir the cream into it to dissipate them then add the vanilla bean and bring slowly to scalding point over low heat till the edges fizz.

Work the sugar into the egg yolks in a ceramic or glass bowl with a wooden spoon or electric whisk until light in colour.

Set a saucepan of water to boil large enough to balance the bowl over it without it touching the water. Lower the heat to reduce to a simmer.

Remove the vanilla bean and slowly stir the hot liquid into the yolk mixture, stirring thoroughly with the wooden spoon. Put the bowl onto the pan of simmering water. Thicken the mixture, stirring it regularly. It is ready when drawing your finger through the back of the spoon separates the cream in two. Take it off the heat at once and strain into a jug or bowl and serve hot or cold.

If you wash the cream off the vanilla pod and dry it out, you can use it again. Or stick it into a jar of sugar to flavour that for other cooking use.

Microwavable version, for 440g/13½ fl oz (A UK pint is just over 19 fl oz, a US pint is 16 fl oz)

600g/20 fl oz single/table or double/heavy cream

6 egg yolks

120g/4¼ oz sugar

1 teaspoon good vanilla extract

Heat the milk (or single/table or double/heavy cream for extra or extreme unctuousness) in a 4-cup glass measure uncovered at 100 percent for 3 minutes. Remove.

Whisk together yolks and sugar. Gradually whisk the hot liquid into them. Pour into the glass measure and return to the oven and cook uncovered at 100 percent for 2 minutes. Remove and whisk vigorously for 30 seconds. Don’t worry if it looks like scrambled egg at the edges - whisking will bring it together. Return to oven and cook 1 minute.

Remove from oven. Whisk vigorously 1 minute. Whisk in vanilla extract then strain through a fine sieve and serve hot or cold in a bowl or jug.

I remember being really upset when I counted the number of flavours at Baskin Robbins. Their tagline was 31-derful flavours and there were always more! They should have stuck with their guns and their puns.