Find more newsletters with opinions and recipes here. If you want to take issue, please Comment.

1 in 5 young Londoners are now vegan. That kind of newspaper report is a ‘Duh’ story, about as revealing as saying 9 out of 10 children prefer eating sweets to broccoli.

Nonetheless, even those who are not hip and Instagramers and living in Shoreditch have cut their meat consumption. Less, perhaps, across steakhouse-prolific USA, but diners in Europe are increasingly understanding that repositioning meat as a treat is a healthier approach for people, the planet - and the animals supplying it.

Henry Dimbleby's National Food Strategy report last week for the British government says we need to reduce the amount of meat we eat by 20-50% for the UK to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050. He proposes a goal he acknowledges British lovers of their Sunday roast and bangers-and-mash will find challenging: a reduction of 30% over 10 years.

“Cows are the new coal,” says Jeremy Coller, Chair of FAIRR. A $5 trillion investor coalition supported by former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, it works to raise awareness of the environmental risks involved in intensive livestock production. Globally, the dairy industry makes up 3.4% of greenhouse gas emissions, close to those of aviation and shipping combined. “If we are to meet the goals of the Paris agreement, countries must also say how they will tackle the high level of emissions from the agricultural sector as part of their national climate commitments,” he said.

Historically, countries across Asia have taken a spare approach to meat. In Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, in wok-cooked recipes that feed a family, just 30g/1oz of meat a head is used to provide flavour, not bulk. Meat isn’t the star of a meal. China and India are considerable nations where highly refined skill in cooking vegetables and pulses renders meat an ingredient of choice not necessity.

Regrettably, they are electing to emulate Western meat-heavy diets. Still, we should take a leaf from their cookbooks, and from the vibrant cooking of the entire Middle East. The way Westerners feed is going to change rapidly in the next ten years. The push is on for us to depend for our protein source not on animals but on pulses, grains and plants plus insects and lab-grown products.

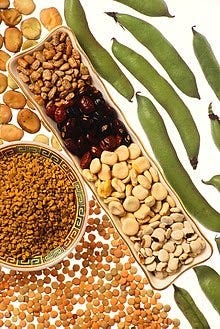

Pulses are stuffed with complex carbohydrates, protein, dietary fibre, folic acid and substantial amounts of iron, zinc, potassium, magnesium and more. Plus, they're cheap and versatile.

On the Indian subcontinent, there are around 60 varieties to choose from. Developed Western nations miss out by not relying on them to the same degree. In street markets across Greece, Turkey, Georgia, the Middle East and India, tin cups of dried lentils and beans are measured out on scales and poured into twists of newspaper to be slowly cooked with local vegetables and turned into loose, thick stews. Eaten with flatbreads or rice, these make nutritious and inexpensive meals.

Most legume dishes begin with a paste. In India, at its most basic, this is made from pestle-and-mortared garlic, fresh ginger, and onions, each believed to have the extra benefit of their own health-giving properties. The next step of cooking in dried and fresh spices from an enormous selection creates a complex dish. The most common additions are roasted cumin, coriander seed, garam masala, chillies, fresh coriander, and tamarind.

The popular kidney bean Caucasian dish ‘lobio’ of Georgia is based on a pounding together of garlic, onion and fresh coriander. Layers of flavour are created with native utshko suneli blue fenugreek, the Trigonella caerulea that grows only in the mountain region (one of the ingredients of traditional Georgian spice mix ‘khmeli suneli’, with a taste also similar to fenugreek), dried coriander, black pepper, and salt.

On the downside and requiring very specific muscular skills to control is the large amount of indigestible fibres in pulses that ferment in the digestive tract, causing gas and bloating.

Heaven forfend if we, not cows, become the methane gas problem. Whether the ozone layer globally would be affected, our social appeal locally definitely could suffer. You can mitigate both if you take the following steps:

Soak pulses overnight and rinse them several times in fresh water before cooking them. Rinse canned pulses, too.

Add to the cooking Indian ajwain or carom seed or Mexican epazote (both of which taste a little like oregano+anise), 1 tablespoon to a large pot to help decrease gas production. Asafoetida also comes recommended: add only 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon to 2 cans of beans. Ignore the reek; it won’t effect the taste of the dish.

Cook pulses until they’re absolutely soft.

Eat them slowly, properly chewing each bite.

Convert slowly to a pulses diet, a few tablespoons at a time.

Also:

When buying pulses, check them for tiny stones. Unscrupulous traders at source are known to add them, particularly to lentils, to increase their weight.

Don’t buy pulses in large quantity unless you know you will be using them regularly. While they don’t have a shelf-life, the older they are, the longer soaking and cooking time they need.

Don't add salt to the water until they have been boiled and softened or they will remain tough.

Like most pulse recipes, this one improves if made the day before. If you switch out the eastern spices for fennel seed or cumin or dried coriander and omit the ginger and chillies, you have a more Mediterranean interpretation. Use flat-leaf parsley instead of fresh coriander.

Serves 6, and left-overs are delicious.

2 tomatoes, roughly chopped

2 cloves garlic, peeled and finely minced

2cm/1in cube fresh ginger, peeled and finely minced

2 small green chillies, finely chopped

2 teaspoons freshly ground coriander seed

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

salt to taste

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

½ teaspoon mustard seeds

2 bay leaves

1 large potato cut in 2cm/1in cubes

1 medium onion, finely chopped

250g/8oz chickpeas, soaked overnight and boiled till soft, 1 cup of their boiling water reserved

small bunch of fresh coriander, leaves only

Put the tomatoes, garlic, ginger, chillies, coriander seed, pepper and salt into a blender and pulse to a paste.

In a heavy bottomed pan sauté the mustard seeds in the vegetable oil, covered. Add bay leaves and fry 1 minute over low heat, then the potatoes and onion. Cover and cook till potatoes are soft, about 10 minutes.

Add cooked chickpeas, the reserved water and the blender paste and stir to incorporate. It will splutter. Raise the heat and keep stirring, 10-15 minutes until the sauce has reduced to thick.

Sprinkle over the fresh coriander leaves and serve with a bowl of rice or soft flatbread.

I’ve been in France a year and I still haven’t figured out potatoes here. The recipe calls for 1 large potato but there are so many varieties! Can you do an article on potatoes? Your research is always so detailed and fascinating to read! Thank you!

The recipe looks good. Is there a name for it? Thank you.