'Frozen' - not the movie: your food. How?

All the recipes you need to make machine-free ice creams, sorbets and granitas

Over the last few years, the early summer invitation I’ve been most feverish to receive has been to participate in the Zeg Storytelling Festival in Tbilisi, capital of the republic of Georgia.

I may have said this before, but go to Georgia before the Russians have conquered Ukraine so turn their attention to increasing their land-grab presence in Georgia. Which sooner or later they will. The country’s courageous population continues regularly to gather in the streets to demonstrate its overwhelming support for joining the EU. But what can be achieved when the increasingly authoritarian Georgian Dream ruling party pushes for closer ties with Russia?

Over the intense, exhilarating, three-day events of each Zeg Festival that bring together storytellers, politicians, journalists, actors, musicians, choreographers, singers, comedians, I’ve moderated panels generally related to the world of food. This year, one focusing on food security brought a celebrated speaker from the UN World Food Programme together with another heading the Georgia branch of People in Need. Up for discussion was how in the future we could eat well without waste in a world stressed by climate change and exploding populations. There was a moment when in considering how to prevent so much of the food we buy going uneaten into landfills it occurred to me one solution might be to reduce the size of our fridges.

Like Nature, humans abhor a vacuum. In the kitchen, we stuff our cabinets with ingredients and gadgets which, if they are stored in the back, will never see the light of day again. In the case of our super-sized refrigerators, we cram them with so much food we don’t get through it all before it rots or the next shopping day comes round.

What if American-sized fridges were made too expensive to buy, except as status symbols in their designer kitchens for all but the super-wealthy few who probably rarely eat anywhere but at impossible-to-get-into restaurants. My own fridge is a small under-counter affair with limited storage. My freezer is its ice box, large enough for an ice cube tray and a sack of frozen peas for hangovers. I buy food fresh three or four times a week

I realise I’m fortunate in living in a city neighbourhood with access to street markets and supermarkets, in common with most communities across Europe. This is an uncommon luxury in the US. I don't need a car for access to meat from the butcher or fish from the fishmonger.

Suburbs and new towns in the UK and the US are given the green light without any allocation in developers’ plans to corner shops, supermarkets, community centres, surgeries or schools, creating a life of isolation from neighbourhood activity for their inhabitants. Why aren’t these legislated for? It’s understandable that if you are forced to get into a car to feed your family, you’re unlikely to be willing to do it more than once a week.

Cavernous refrigerators probably crammed with more than is needed to feed a family for seven days account for the shocking one-third of nutritious food that, in the developed world, gets chucked into landfills.

Obviously, we can’t do without refrigerators. But how large to they need to be?

It was a Scottish physician and academic, William Cullen, who first demonstrated the cooling effect of rapidly evaporating a liquid into gas to chill temperatures, in 1748. But he didn’t pursue his discovery. The impact it could have on chilling comestibles and drinks was left to Jacob Perkins to reveal. An American inventor, he is credited with inventing the first vapour-compression refrigeration system in 1824, receiving a patent for his "Apparatus and means for producing ice, and in cooling fluids", which laid the foundation for modern refrigeration. Then research from 1873 to 1877 by German professor Carl von Linde on heat theory led to his invention of the first reliable and efficient compressed-ammonia refrigerator. Replacing ice in food handling, it was taken up enthusiastically by commercial enterprises like meatpacking plants and breweries.

Originally, ice harvested from frozen winter lakes rivers and cut into bricks had been stored by the wealthy in pits underground to preserve perishable items like meat. Huts built over them trapped the rising cold air, keeping less volatile foods fresh.

With people moving away from the countryside into cities, a solution for keeping perishable food cold was vital. But it wasn’t until 1913, nearly 60 years after the commercial world had begun using refrigerators, that American Fred W. Wolf invented the first home electric refrigerator, featuring a refrigeration unit on top of an icebox.

In 1918, William C. Durant, a founder of General Motors, invested in the Guardian Frigerator Company of Fort Wayne, Indiana, which adopted the name Frigidaire and developed a self-contained compressor for the first home refrigerator. Five years later, Frigidaire began mass production of refrigerators for the domestic market.

Once Freon (a compound of predominantly chlorofluorocarbons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons, used in air conditioning and refrigeration systems and now banned for their impact on ozone depletion and global warming), was introduced in the 1920s, the domestic market for fridges took off. By the 1940s, home freezers had been introduced, creating another market making frozen foods available to the masses.

In the US, that is.

By 1948, more than half American homes owned a refrigerator, but in Britain, only 2 percent of households. And while UK fridge ownership had increased by 1970 to 60 percent, the only freezer most Brits had was the frosted crystals-seized little box at the top of their modest fridges.

My mother used her small fridge to store cooked leftovers and limited perishables for immediate cooking. As people become more affluent, so their fridges began to grow, to accommodate luxuries not necessities, from canned drinks, juices, yogurts, salad leaves and ready-chopped vegetables, chicken joints and meat cuts.

Bigger fridges demand more content options. Cargo ships cross and recross oceans to bring us vegetables unfamiliar to our grandparents, stored in transit in massive shipping cold storage facilities to be sold to us as ‘fresh’.

With rising temperatures, we’re going to need refrigeration to keep bacterial reproduction at bay and our food safe. But if we had easier access to local food supplies, we might be able to consider smaller fridges and change to shopping habits that keep waste to a minimum? Developers and town planners willing, of course.

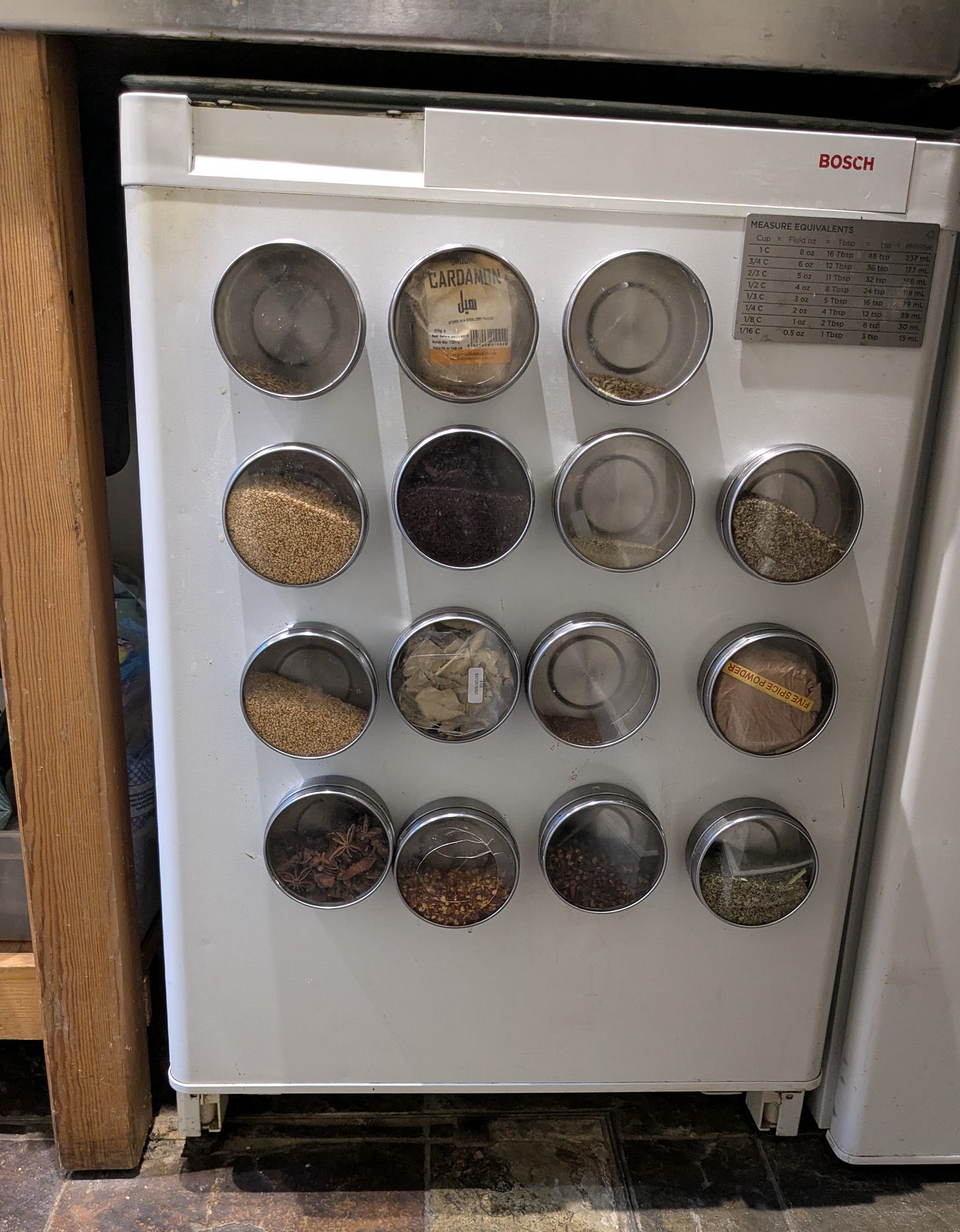

Hacks for iceboxes and freezers: Fill ice cube trays with chopped, damp (so they stick together) fresh herbs. Once frozen, decant the cubes into freezer bags to add to soups, stews, anything. Same process with very concentrated stocks which, once unfrozen, you can stretch out with water or wine. Freeze lemons and limes. You get more juice from an unfrozen citrus fruit. Egg whites: they won’t froth quite so much but add them to a fresh one or two and they’ll billow. Egg yolks: unfreeze for mayo and liaisons and pastry washes. Make ice cubes for cocktails from chopped herbs, berries or citrus zest and freeze in water/wine/spirit - though be wary of the latter unless you’ve my liver/joie-de entertainment. If you have an irregular guest who desires a specific jam that you don’t like for their breakfast toast which will grow blue hair once its jar is opened, fill an ice cube tray with it, freeze it (though it will only become soft not stiff), bag it and wait for the next visit to unfreeze a couple of cubes.

Meanwhile, summer is here. You really don’t need a machine to make ice cream or sorbets. Scroll down to the bottom of these stories for recipes for honeycomb ice cream, strawberry sorbet, yellow plum sorbet and other fruit equivalents.

For no churn, no machine Honeycomb ice cream:

For yellow plum and other fruit sorbets:

For strawberry and other granitas

For no machine Sea buckthorn sorbet:

I so wish we had more markets and food shops locally. We have two small supermarkets neither of which has a great range of fresh produce and a butcher. More cafes than any town deserves. The nearest market is once a week and a half hour drive to get there. I buy my meat and eggs direct from farmers as often as possible but storing the meat needs a large freezer. I grow as much as possible but high up a hill in North Wales that’s not as much as I’d like.

storytelling festival looks so fun!!