Those who’ve moved away from eating livestock meat to plant-based meat for environmental or anti-feedlot reasons may have to reconsider their stance.

At the University of California, Davis, the campus associated with agriculture, food, wine, the environment and more, a research study now suggests that cultured meat production could have a far worse impact on climate change than conventional beef production, raising global warming by up to 25 percent more than regular beef. At fault is the ‘meat cells’ production process.

Already sales of cultured beef have flatlined, rejected by consumers for its disappointing taste and texture. Still, those concerned for the state of the environment are nevertheless prepared to put up with a lesser eating experience for the sake of the globe or the cows chained side by side along miles and miles of concrete feedlots.

Livestock production is thought to be responsible for 18 percent of global greenhouse gases. It has a massive impact not just on deforestation, particularly in the Amazon rainforest, but in depleting water supplies. A cow raised for eating needs one gallon of water per 100 pounds of body weight - around 24 gallons daily. But if it turns out the stability of global temperatures could be even more vulnerable to plant-based meat production, consumers will have little incentive to keep supporting it.

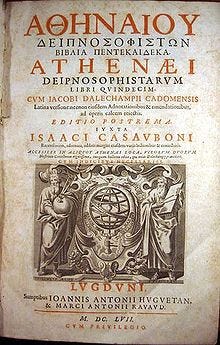

Analogue meat - and fish - is nothing new. Tofu, made from soybeans, was invented in China in 206 BC during the period of the Han dynasty and known as ‘small mutton’. In 3 AD, Anthenaeus writes in Deipnosophists of the preparation of a mock anchovy, shredded turnip mixed with oil and salt and poppy seeds and shaped into a fish.

Soy bean and wheat gluten alternatives to meat have been part of Chinese and Buddhist cultures for centuries. In 1877, John Harvey Kellogg created meat replacements from soy, nuts and grains for patients at his vegetarian sanitarium, Battle Creek. In 1898, publication of The Golden Age Cook-Book by Henrietta Lathan Dwight included meat-substitute recipes such as ‘mock chicken’ and ‘mock clam soup’. Vegetarian Sarah Tyson Rorer brought out her Mrs Rorer’s Vegetable Cookery and Meat Substitutes in 1909. In 1945, soy beans were declared by Mildred Lager, American pioneer of natural and health foods to be “the best meat substitute from the vegetable kingdom, they will always be used to a great extent by the vegetarian in place of meat." Food shortages during the first and second world wars also encouraged an interest in alternatives to meat.

The UC Davis study has not yet been peer reviewed but it is intensive. Its scientists studied natural livestock from birth to abattoir, and compared its effect on the environment with that of the growth cycle of cell-based meat. They included the impact of both on production of water, land, minerals and crude oil use, as well as emissions of carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxide gases into the air.

While cultivated meat depends neither on land nor water, it is produced from animal cells requiring a combination of tissue engineering, molecular biology, biotechnology and synthetic processes to grow. But that growth is dependent on E8, a specific, highly-refined medium that provides a crucial combination of nutrients and growth-media.

The UC Davis scientists found that E8 could lead to greater global warming than natural beef because of the type of emission it creates: while the methane gases emitted by living cows dissipate after a few decades, the CO2 emissions involved in E8 cultured meat growth hang around indefinitely.

If you speak Science, what the study says is, “Without purification of the growth medium components, the global warming potential of the glucose consumption rate is approximately 25 percent greater than reported median of global warming potential of retail beef.”

But, meanwhile, there is a simple solution to reducing gas emissions: don’t buy so much food.

A quarter to a third of global greenhouse gases come from food production systems, and half of those from food loss and food waste. ‘Food loss’ covers attrition at the points of production, storage, processing and transportation. As to ‘food waste’, in 2017, the most recent survey, 9.3 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions were created by food waste alone.

That’s more than double previous estimates.

Of ‘food waste’ emissions, 11 percent comes from food thrown away by wholesalers, retailers and traders. Just over one third - 35.5 percent - comes from you and me, developed world consumers throwing food away uneaten into landfills. This one-third that we make up is a quantity so huge that if you viewed its size as a nation, it would be the third greatest emitter of greenhouse gases after the US and China.

So if you want to eat meat, for the sake of the environment and for the wellbeing of the cow, perhaps you should go back to buying it from an independent pasture-farm-to-butcher source. And make use of every part of the creature, from oxtail to tongue and all the edible offal in between. But don’t buy it too often - and only buy enough that it will feed you and not your garbage can.

With grilling season just around the corner, I’ve learned over the years that the best burger comes from doing the least to it and doing it all yourself.

Buy a piece of chuck or braising steak, the meat from around the shoulder of the cow, and mince or grind it yourself. Better still, take a very sharp cleaver or knife. With it, cut slices across the grain as skinny as you can then bunch the strips and do it again crosswise. Next, chop the mass as if it were herbs into mince. This way, you get chew, not mush. Whichever way you choose, do it while keeping the meat as cold as possible. Don’t salt the meat until you’re just about to grill it, then season it liberally. Salt dissolves muscle protein and encourages squelchiness, particularly in ground meat. Pepper it liberally, too. Handle the meat as little as possible, forming it very quickly into a pattie. Once on the grill, turn your burger as often as you want. It encourages more even and faster internal cooking but it really doesn’t matter if you don’t. Then arrange with whatever goblins or totems you trust to give you a sunny day to eat it, outdoors with friends.

Very interesting and informative- as always. I only recently realised that look and taste alike meat could actually be made from cells- which I see is entirely different from meat substitutes that also gt called meat. So climate change issues aside- which you make a convincing case for- I wondered if down the track they will find that they have some awful health implications too- given they are playing around with cells.

Good analysis. Good recipe too.