Find more Tabled newsletters with recipes here.

In preparation for the arrival of the Good Fairy, an event I still believe to be imminent, I draw up lists of my Three Wishes.

When I was little, these focused on presents Father Christmas had failed to deliver. In my teens, my hopes were pinned on excelling at slide guitar without any lessons and physical perfection. (There’s two wishes in that.) In my 20s, I wanted the ability to speak every language, a heart-breaking singing voice, and a polished aluminium Airstream.

With maturity came less fanciful choices - the freedom to consume and drink everything to no physical effect (which for quite some time appeared to have been granted), and happiness and general stability for my nearest and dearest.

Frankly, these days I’m finding stability tedious. Accordingly, I have simplified my three wishes: Dear Good Fairy, for wishes 1), 2) and 3) please may I have all my collagen back.

No matter what it promises on the cosmetics tubes, you cannot apply collagen externally.

Take a lesson from chefs. It’s not only proponents of nose-to-tail eating, like chef Fergus Henderson, founder of St John’s Restaurant and high priest of roasted bone marrow on toast, who understand the value of collagen in flesh.

It’s any chef watching their bottom line and doing their best not to waste a single element of a carcass.

And it’s also respect. As Fergus Henderson observed, “If you’re going to bang an animal on the head it’s only polite to eat it all.”

Consider the cow. It double-masticates roughly 36kg/80lbs of food a day, in up to eight meals. That’s the weight of a queen-sized bed with mattress and headboard. It drinks 30 to 40 gallons of water - or 1120 cups of tea, if it could grasp a mug.

From a social responsibility point of view, wouldn't you think we would not want to waste a single atom of a creature that consumes so much of our resources on a daily basis?

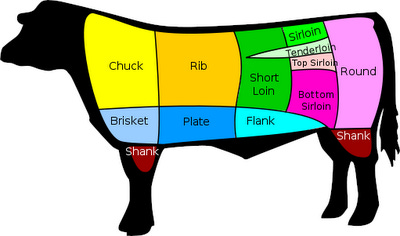

No diner orders chewy meat. Tenderness is most easily achieved by exposing an expensive cut of unworked tissue, like a steak or rib roast, to high heat. But the larger portion of any beast is given over to well-exercised, tough flesh, its muscle fibres held together by collagen.

Cooked dry at high temperatures, the collagen fibrils holding these muscle fibres together shrink. The result is tough meat.

But long cooking at low temperatures develops not only the meat’s flavour but its melting tenderness. Braised slowly in liquid at around 70C/160F, collagen begins to render inside the meat fibres, breaking down into a rich gelatin.

I’m not anticipating being cooked, but now can you see why I want my collagen back? Melting tenderness. In humans, collagen keeps skin toned. And taught. And plump.

It’s also an agent against stress and inflammation, though I’m not so much in pursuit of that advantage. Beauty product manufacturers, of course, are keen to press the point, cannily pretending their clients are focused on health, not vanity. They also underline its ability to improve poor digestion and correct cartilage and gastrointestinal tract damage. Meh.

In meat, more persuasive is the fact that collagen is most abundant in the cheapest cuts. If you’re going to buy meat at all, this allows you the leeway to buy it from organic butchers.

Organic* meat is worth the extra expense. You don’t need reminding of the impact intensive farming has on the welfare of the beasts, biodiversity, and the destruction of the environment.

Look to the US. In 2019, the USDA Census of Agriculture revealed that 98.74% of farmed animals are raised on intensive factory farms. (You probably don’t want to click that link.)

In 2018, nearly a dozen sites across England were found to be operating intensive farming practices, with the largest farms fattening up to 6000 cattle annually. The number is likely to rise with Brexit trade deals.

Scientists warn that an increase in intensive farming creates a perfect breeding ground for further pandemics, should you be seeking more evidence in favour of organic meat.

If you need convincing about the effects of collagen, make Ossobuco, a Lombard speciality usually served with risotto alla Milanese. The rice of the Piedmont also being suited to long, slow cooking in a little liquid, it’s a pairing made in heaven.

A cross cut of rosy veal shank exposes the osso (bone) with the glory of bone marrow nestling in the buco (hole). The slowly braised shanks are sprinkled just before serving with gremolata, that finely chopped mix of garlic, parsley and lemon zest which, eaten with the bone marrow, is a pairing made in heaven.

Oh. I already said that.

Veal fell out of favour with the revelation of the inhumane tortures calves were subjected to. They were packed into crates, often so confined they were unable to stand, to achieve flesh as white as pork. Rosy veal is raised without cruelty. Look for cuts described as milk-fed, which should mean the calf has remained with its mother.

Find a living breathing butcher with whom you can discuss how theirs has been raised - not a question you can ask a cellophane package.

Ossobuco goes in the oven for 1½ hours, a bonus when you want to be out of the kitchen and with your friends.

Serves 4

Preheat the oven to 175C/350F

Flour for dredging the meat, seasoned with pepper (salt will dry the meat out)

4 cuts of veal shin, 4.5cm/2in thick

60ml/¼ cup olive oil

55g/2 oz butter

2 medium onions, peeled and diced

2 stalks of celery, diced

2 small carrots, washed and diced

145ml/¼ pint white wine

2 tablespoons tomato paste

145ml/¼ pint stock

400g/14oz fresh tomatoes, blanched, skinned and chopped, or 1 400g/14oz can peeled tomatoes

1 large sprig fresh thyme

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Bunch of flat leaf parsley, stalks discarded

zest of 1 scrubbed lemon

1 large clove garlic, peeled

Dredge the meat in the flour and shake off the excess. Brown the pieces in 3 tablespoons of oil. Set them in a pan you can put in the oven, to prevent the marrow from falling out. Wipe out the frying pan. Add the remaining oil and the butter to gently saute the mirepoix (onions, celery and carrots) till soft, about 15 minutes. Pour in the wine, scraping up the vegetable caramel. Raise the heat and reduce till almost gone then stir in the tomato paste. Dilute with the stock, season, add the tomatoes and bring to the boil. Pour over the veal, add the thyme and cover tightly. Place in the oven to braise for 1 ½ hours. Check during cooking the liquid hasn’t evaporated. Serve from the pan with the gremolata, made by finely chopping the parsley leaves, garlic and the zest of the lemon together, sprinkled over the top. Eat with risotto Milanese, polenta or pureed potatoes.

*Organic here refers to the UK definition, not the US definition which doesn’t meet UK standards.