Family traditions create great glue, generally necessary at this time of year when expectations and matching tensions run particularly high. At Christmas, mine has followed the same one ever since I was old enough to recognise it was a tradition.

Our Christmas feast was an evening affair to keep us all day long on tenterhooks*. So how to sate the post-breakfast hunger pangs between the chilly afternoon walk we resented going on but ended up relishing, and the early evening unwrapping of presents? Around midday, after Christmas Carols service, a tray was set before the roaring fire, laden with glasses of Buck’s Fizz, a plate of thinly sliced and thickly buttered brown bread, quarters of lemon, the essential jar of Cayenne Pepper, and a HUGE platter of smoked salmon.

Smoked salmon is a celebratory fish. It is not to be confused with lox, a word which comes from ‘lax’, the Yiddish word for salmon. Lox is celebratory, too, with bagels and cream cheese a staple of the best brunches. But it is not smoked. It is long-cured in a salt brine.

The difference between hot-smoked and cold-smoked salmon is obvious from their colour. The opaque pink of hot smoked salmon is achieved by cooking, rather than smoking, the fish, directly over a fire at around 66-77C/150-170F, in a short space of time.

Smoked salmon is cold smoked, typically at half the temperature - under 30C/90F. Cold smoking does not cook the fish and results in a delicate silky texture, while hot smoked salmon is flaky.

Before the smoking process, cold-smoked salmon is also cured in a brine, to increase its ability to absorb the smokey flavour. It’s then slowly smoked for hours, sometimes through the night, hung high inside a kiln (in the old days a brick one) over smouldering damp sawdust, in many smokeries from old oak whisky casks, in lines on hooked racks or tenters*, the origin of the phrase ‘on tenterhooks’. (Nice, eh?) Industrial production uses cheaper woods and favours less exposure to smoke for a blander style. Even with today’s modern steel kilns, in some artisan smokeries workers still climb up to the tenters to individually hang the lines of fish. How long the fish smokes is determined by the master smoker who checks with his experienced nose for the best smoking conditions.

Smoked salmon is one speciality where it really is worth your while going for the more expensive artisan option.

In Scotland - still the source, I would argue, of the best smoked salmon - the habit of smoking fish can be traced back to the 11th century. It’s believed to have been brought over by the Vikings as a more edible method of preserving fish than drying them.

Records of smoking salmon go back even further, well before the Greek and Romans. There is a life-size carved depiction of a salmon on the floor of a cave in Les Eyzies in the Dordogne region of France that dates to 22,000 years ago.

It is believed that salmon, along with wild boar and reindeer, would have been smoked for winter supplies.

London’s East Enders claim the idea of smoking salmon and other fish was brought to the UK by Jewish immigrants in the 19th century, who imported Baltic salmon in barrels of salt water and brought the technique of salmon smoking from Russia and Poland. It turned the East End into the hub of a large salmon smoking industry which is now beginning to return to the area with small ventures creating different flavoured smokes (gin-and-tonic, if you must), in the ‘boutique’ manner so treasured in that part of the capital .

Historically, salmon was a popular and prolific London fish, caught in nets in the River Thames. In 604 AD, to a small chapel to be dedicated on the banks of the river, salmon fishermen ferried across a man they later swore was St Peter. When, in 960 AD the decision was made to found a riverside cathedral, the chapel was picked as the site for its association with St Peter and the salmon fishers, and so Westminster Abbey was built. Every year since, London’s Fishmongers’ Guild donates a salmon to the Priory of Westminster.

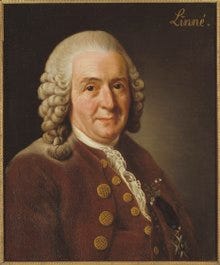

When the Romans conquered Gaul and discovered salmon, it was described as salmo, the word for leaper. The Latin name was salar, also leaper. Middle English turned the word into samoun. When, in the 18th century, Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist who formalised the modern system of naming organisms, was codifying the name of the species, he combined the two to create their scientific name, Salmo salar.

With out of control commercial fishing depleting stocks of wild salmon, these days smoked salmon is produced most commonly from farmed salmon. Go on line and order some from any artisan producer, preferably Scottish. Then mix horseradish into some sour cream to smear over these simple ersatz (because of no yeast or proving) blinis to go with the salmon. Or just eat it on its own - with buttered and thinly-sliced brown bread, a squeeze of lemon juice and a sprinkle of Cayenne pepper which I assure you is not optional and can’t be replaced satisfactorily with black pepper.

75g/5 tablespoons buckwheat flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

pinch of salt

1 egg

150ml/5 1/4 fl oz milk

butter for frying

Put the flour, baking powder and salt into a bowl into a jug and stir to mix.

Beat in the egg then whisk in the milk to a smooth paste.

Heat a large frying pan until hot. Smear over a little butter (still wrapped). Drop teaspoons of batter onto the pan to make small blinis. As with the best crepes, you will probably have to throw out the first one. I’ve never understood this phenomenon but just accepted it.

Once bubbles appear on the surface of the blinis, turn them over and cook the other side. Set onto a warm platter and cover with a tea towel while you smear more butter and repeat with the remaining batter.

Happy Christmas or whichever observance you celebrate which may just be a Monday off work. That’s worth a smoked salmon feast.