In one of my career variations, I was the Style Editor on the magazine of Britain’s largest Sunday newspaper. One week I’d write that lavender was the colour of the moment, painting up a studio in the shade for a photoshoot of furniture and ‘must have’ bits and bobs key to attaining The Look. In the following weekend’s issue, readers would discover that the colour of the moment was now sage. Repeat the above, only this time in grey-green.

At least in the field of food, trends last marginally longer. Though not by much. In my next job, Food Writer for an international news agency (no, there isn’t an obvious link between decor and nosh, but expert knowledge is only a phone call away), one of my remits was to write up official food pronouncements. There was the year when the Food & Drug Administration declared nothing was worse for our health than butter. If we wanted to avoid appalling outcomes from cancer to heart attacks, we needed to ditch it immediately and replace it with margarine or oil-based spreads. This led to an explosion in dairy-free brands with startling names. My favourite was Unilever’s I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter which I shortened to Snot Butter.

A year later, the FDA retracted its directive, finding that by hydrogenating vegetable oil, margarine’s saturated fat content increased, and produced unhealthy trans fats besides. It discovered manufactured products were far more unhealthy than Nature’s straight-from-the-cow bounty with its side helpings of vitamins A and E, and riboflavin, niacin, calcium and phosphorus.

Could we not have told the FDA that? After all, our prehistoric ancestors didn’t appear to have suffered from any adverse effects from eating butter. Yes, butter was an established part of their diet. Residues of milk fats have been discovered on pottery found in northwest Turkey dating back to around 6500 BC.

Since it was removed from the naughty step, butter has come on by leaps and bounds. There is hardly a recherché restaurant that doesn’t create its own, with someone in a cool backroom busy churning cream into an unctuous treat sprinkled with salt crystals that emerges from the kitchen in a hand-crafted bowl with wedges of warm sourdough, to welcome the diner like a suitor with a rose. The stellar Nora Ephron, American writer, journalist and screenwriter, had the right idea: “Nothing like mashed potatoes when you're feeling blue. Nothing like getting into bed with a bowl of hot mashed potatoes already loaded with butter, and methodically adding a thin, cold slice of butter to every forkful.”

This year, global revenue for butter is expected to hit $46 billion. Accounting for every smear of that is Big Butter Biz, brands like the Danish Lurpak and Ireland’s Kerrygold, the second most sold butter in the US. But now small batch makers are looking to make serious inroads into the conventional butter market. Even my local supermarket chain sells a bijou French butter with salt crystals at an elevated price.

There’s clearly a market for ‘boutique’ butter. Chef Thomas Straker, born on a small farm in Herefordshire, and behind Notting Hill hotspot Straker’s and the recently launched Flat Bread in Battersea Power Station’s Arcade Food Hall, is joining best-friend-from-school Toby Hopkinson, who has several start-ups behind him, to launch All Things Butter.

They secured pre-seed funding of more than £530,000 and have teamed up with Brue Valley Farm in Somerset, who still use traditional butter making methods, twice-churning the butter for the perfect extra-creamy texture. 1 percent of its revenue will be directed to supporting British farming. So far, along with salted and unsalted butter, they’re offering Chili flavour and Garlic & Herb.

If you prefer plant-based butter, Original Better is a Netherlands butter that Willicroft, the Netherlands plant-based cheese company, describes as ‘butter, but better.’ Made from soybeans, shea butter, rapeseed oil, sunflower lectin, coconut oil, salt and carrot juice (for its colour, I’m guessing), it uses a fermentation process that replicates butyric acid, the key component of dairy butter.

Don’t imagine you can avoid plant-based butter alternatives. They may appear unannounced in your pastries. Bunge (I’m grateful for that ‘e’) is a company that has developed a fat called Beleaf PlantBetter, made from coconut, cocoa butter, rapeseed and lecithins. It targets food manufacturers and bakers and is presumably cheaper to use in their products than dairy butter. Its retail version is called Eleplant. Ho ho. I shall be reverting to the word that name is based on.

With Christmas, Hanukkah, the winter solstice, Kwanzaa, and Shōgatsu coming up, butter is likely to have a larger than usual presence in the fridge. Turkey requires lashings on or under the skin. Shortcrust pastry for mince pies demands it. Yule logs and other sumptuous cakes would be drear without it.

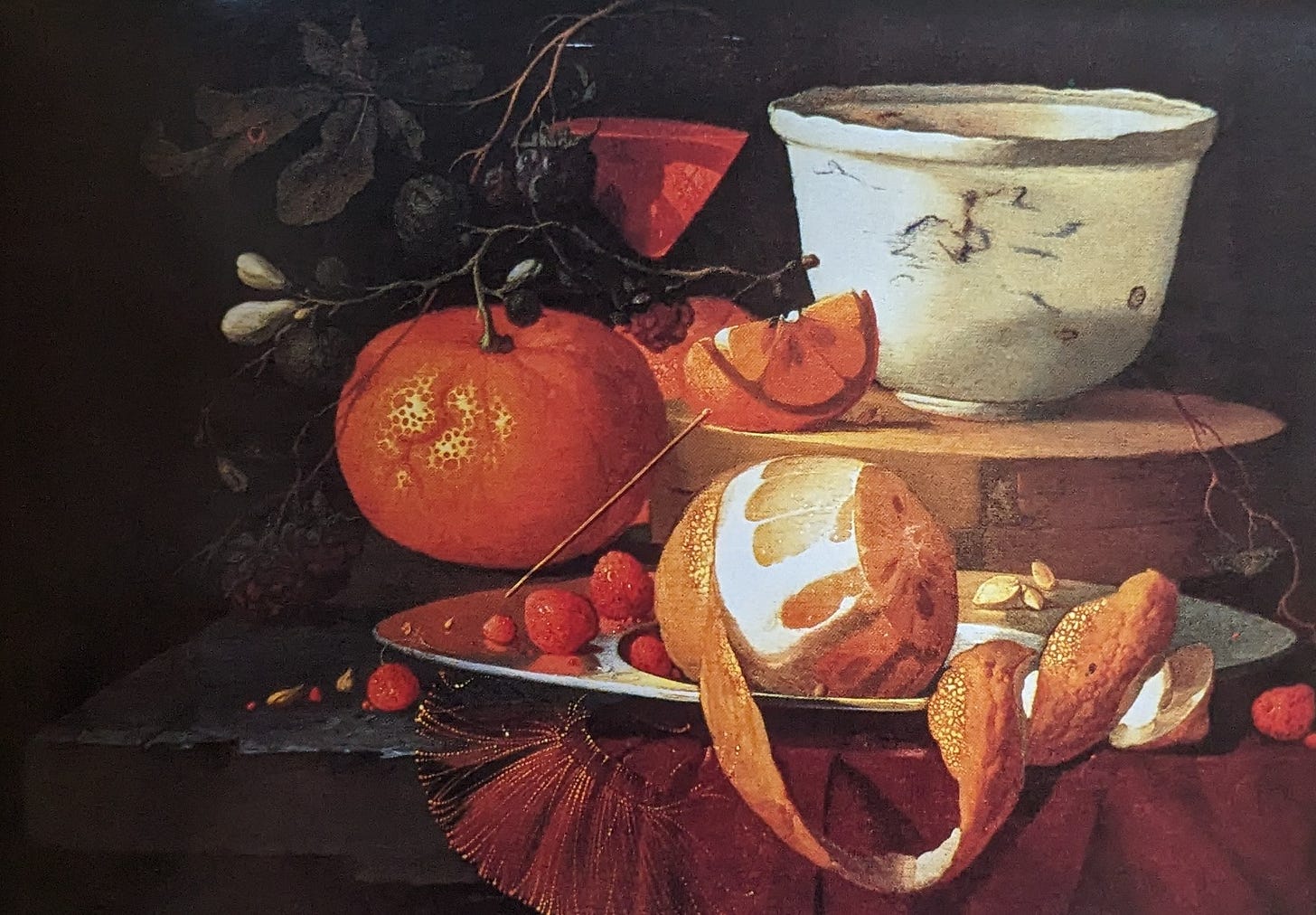

Jane Grigson, a splendid English cookery writer whose weekly columns and regular books helped promote British food, gave a recipe in her glorious read Food with the Famous for Butter’d Oranges, which would make a wonderfully festive dessert.

8 sweet oranges

5 egg yolks (make meringues with the whites)

60g/2oz caster/superfine sugar

Teaspoon triple-distilled rosewater from a Middle Eastern supermarket

125g/4oz unsalted butter

150ml/5fl oz double/heavy cream whipped into just-before soft peak stage

Large piece candied orange peel

Turn six oranges on to their stalk ends. Using a zigzag cut, remove lids from each starting about 2cm/1 inch down. Scoop out the pulp with a pointed teaspoon and save for other dishes. Grate the peel of the two remaining oranges, and squeeze their juice into the top of a bain marie/double boiler or basin set over simmering water. Beat in the yolks and sugar and the grated peel. Stir until very thick.

Remove the top bowl to a large bowl of iced water to cool the mixture fast, stirring. Once cooled a little, take out of the iced water and stir in the rosewater then the butter in small bits. It should soften into the mixture, rather than melt. When the mixture is smooth and quite cold, fold in the half-whipped cream. Chill until very thick, add the shredded candied orange peel and spoon into the orange shells then replace their lids and serve.

To make candied orange peel, cut 4 large unwaxed oranges into 8 wedges then scrape off the flesh, leaving just the peel and pith. Cut each wedge into 3-4 strips.

Put the peel in a pan and cover with cold water. Bring to the boil, then simmer for 5 minutes. Drain off the water then cover with fresh water. Bring to the boil and simmer for 30 minutes.

Drain the peel through a sieve over a bowl, reserving that cooking water. Measure it out. Add 100g/3¾ oz to each 100ml/3¾fl oz of water. Pour into a pan and gently heat, stirring to dissolve the sugar until the peel is translucent and soft, about 30 minutes. Leave to cool in the syrup then remove peel with a slotted spoon and lay over a wire rack set over a baking sheet. Put in the oven at the lowest setting for 30 minutes to dry.

At this point, you can add the orange peel to the Butter’d Oranges recipe. But if you would like to make a gift of sugared orange peels, carry on:

Sprinkle a layer of sugar over a sheet of baking parchment. Toss the strips of peel in the sugar, a few at a time, then spread out and leave for 1 hour to air-dry. Pack into an airtight storage jar. Will keep for 6-8 weeks in a cool dark space.

Hot melted butter on corn with salt oh the cob is hard to beat.