The London borough I live in could never be described as deprived. Yet increasingly, the range of fresh produce in my supermarket has shrunk. It’s not just a loss of food from overseas, no longer stocked because of post-Brexit import taxes plus the reams of forms now required by the British government for goods to enter the country. Responsible in part is British farming. In steady decline since its 1995 peak and now fighting rising fuel and production costs and diminishing financial returns, it can’t step in to cover the loss.

But the other threat to our food supply is climate change.

We read endless reports of its destructive effect upon wildlife and biodiversity. What we read less about is its impact upon the crops we grow. A recent report from Action on Hunger labels eight of them (so far) ‘endangered’. Read fellow-Substacker Kate Walker on the depletion of supplies of rice and its effect on the peoples of southeast Asia, where around 60 percent of daily calories come from rice and, in developing countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, as much as 70 percent.

The industrial world may be able to substitute other starches for rice without too much discomfort, since it doesn’t constitute a vital staple anywhere from Moscow to Paris, London to New York. But we’re losing potatoes to the weather. Maize, too, which feeds people and livestock. Both need a steady supply of water.

Cocoa and coffee are also on the list. Cocoa needs constant conditions to thrive. Yet Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana in West Africa, responsible for half the world’s production, are experiencing erratic rainfall and winds. Moving the crops to higher elevations will likely lead to deforestation. Coffee, a crop essential to smallholder farmers, is predicted to decrease 25 percent in Ethiopia by 2030. How ever will Millennials, summoned to return to work in offices, cope without their cup of java to propel them from their bedroom desks?

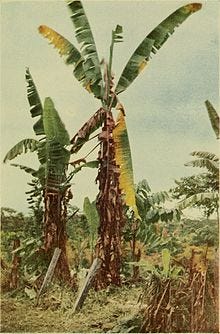

Listed, too, are bananas and plantains. Like coffee, they are cash crops. Production of the latter has fallen 43 percent over the past 20 years, threatened by diseases on the increase through rising temperatures.

Before bananas in the wild “go extinct”, as reported in a study published in Frontiers in Plant Science, experts at the Alliance of Biodiversity International & CIAT have been pitched into identifying the genes in the banana’s family tree. They hope to breed varieties better protected against Panama disease and Fusarium wilt, both increasing in an industry worth $8 billion that produces 100 billion bananas a year.

Wheat, too, is in decline. With enough rainfall, production in cool regions like Europe and the USA may see an increase in yields of 5 percent. But in nations like India, Central America, and Africa, they are predicted to decrease by at least 3 percent. While 10 percent of the world’s supply of wheat comes from Ukraine where the war looks unlikely to end any time soon, India produces 14 percent. Loss of production in growing areas now experiencing increasingly hot and dry conditions will have a significant impact on the families growing the grains, and on the millions relying on wheat for sustenance.

Even as crops grow, rising temperatures will lead to increased concentrations of CO₂ in the air which in turn create lower levels of iron, zinc, protein and other nutrients in staples like soy, wheat and rice, leading to malnutrition. Higher temperatures won’t only alter crop yields but how crops can be stored in increased heat without infestation from pests or mould.

Back to rice: if the planet’s average temperature hits 2.5C/36.5F above pre-industrial levels by the end of the 21st century, half the Mekong delta, the world’s biggest rice exporter, will be under water.

Is it likely any of these populations, reliant on farming for their survival, are going to stay put and watch it happen? The UK, Europe, and the USA are already struggling with waves of immigration. What will occur when whole nations can’t eat? In the movement of people, we ain’t seen nothing yet.

I work wage-free (‘volunteer’ can be open to condescension) at a food distribution charity. Once providing predominantly raw food, we have been obliged to open a kitchen, since too many recipients of our ingredients, very many of whom have jobs but on minimum wage, can now only afford to turn on a microwave. Here is a hearty, nutritious soup, with canned vegetables, quickly prepared, appealing to any group of people. It serves 4 but doubled up allows for food across several days whose flavour can be altered by the addition of different vegetables, spices, fresh herbs, or toppings if available. Cubes of meat or chicken can also be incorporated, frying them just after the onions and garlic, to create a substantial stew. It improves with reheating.

1 tablespoon oil (olive if you have it, vegetable if not)

1 onion, peeled and roughly chopped

1 large clove of garlic if you have it, peeled and finely sliced

2 celery ribs, chopped, or half a fennel bulb (optional, but both are often in the ‘Reduced’ crates)

2 teaspoons ground cumin (a supply of cumin, fennel and coriander seed, red pepper flakes is a good investment)

½-1 teaspoon red pepper flakes

600ml/20 fl oz hot vegetable stock (from a Knorr jellied Stock Pot or cube)

400g/14 oz can chopped plum tomatoes (buy cheaper bashed cans whenever you see them)

400g/14 oz can chickpeas, drained and rinsed (that acquafaba liquid can be made into vegan meringues if you are able to use your oven)

100g frozen broad beans if you own an icebox (canned and drained can substitute)

salt to taste

zest and juice ½ lemon (a teaspoon of vinegar could substitute)

large handful coriander or parsley (a luxury and optional. A tablespoon on each bowl of labneh or yogurt is a fine alternative or addition if you have any)

Heat the oil in a large saucepan. Saute the onion, garlic and celery over medium low heat until softened, stirring frequently. Stir in the cumin and red pepper flakes and saute one minute more.

Raise the heat, then add the stock cube and 600ml/20 fl oz water, tomatoes, and chickpeas. Simmer about 8 minutes. Add the broad beans and lemon juice and cook 2 minutes more. Season with salt to taste (the stock cube is salty). Top with lemon zest, chopped herbs or yogurt.

I have been saying for years (and a very unpopular view it is, too!), that whatever we do to counter global warming, from solar panels to electric cars to the hated ULEZ, is too little, too late; the main thrust of our efforts and researches MUST go into finding ways of coping with the inevitable. 'Saving the planet' is arrogant nonsense - the planet has been here before, it is more than capable of surviving; it is the future of the human animal that concerns us. And the first thing we should tackle is the problem of feeding a burgeoning human population.

I love soup, it's very much a staple in my house. My daughter works wage-free (love it!) in a community garden, which also has a food bank, so I shall forward the recipe to her, as a handout for the customers.

As always, many thanks for an interesting and informative article

Thanks for the link! The situation in the Mekong Delta is even worse than you write, a lack of sediment linked with upstream damming has the entire Delta projected to disappear into the sea by the end of this century (best case scenario) or as soon as 2035. In Vietnam alone, 17 million people will be made homeless/lose their livelihoods/die.